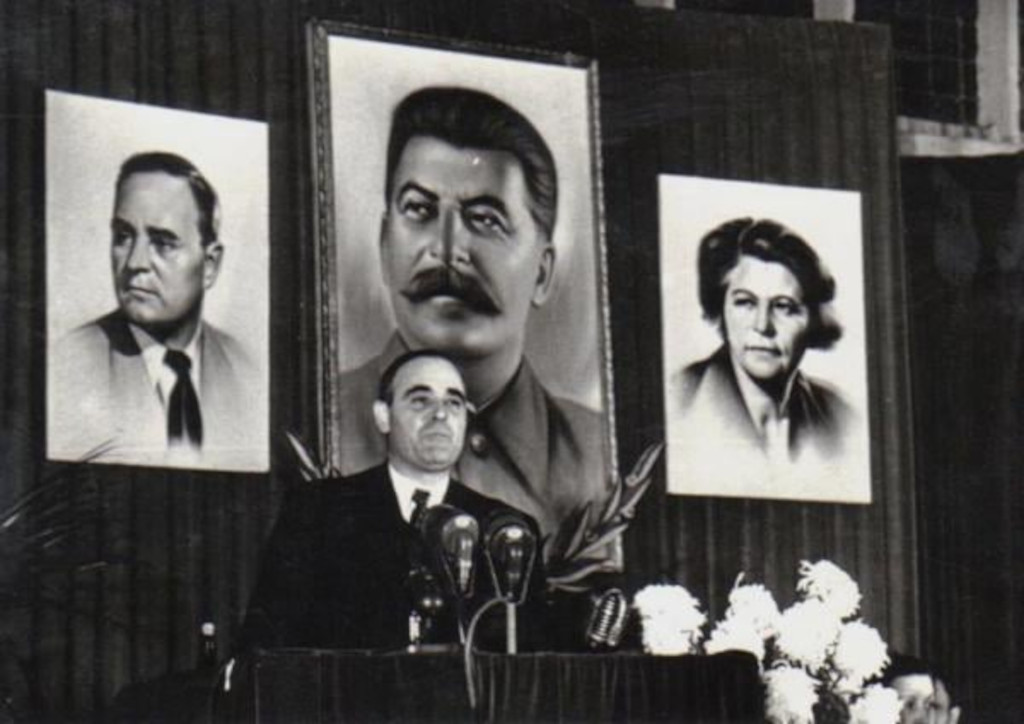

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej speaking at a workers' rally in Nation Square, Bucharest after the 1946 general election.

Romania

In a speech before the Parliament of Romania, President Traian Băsescu stated: "the criminal and illegitimate former communist regime committed massive human rights violations and crimes against humanity, killing and persecuting as many as two million people between 1945 and 1989". The regime deported hundreds of thousands of people and killed by assassination.

The Socialist Republic of Romania was a Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist state that existed officially in Romania from 1947 to 1989. The country was an Eastern Bloc state and a member of the Warsaw Pact with a dominant role for the Romanian Communist Party enshrined in its constitutions. As World War II ended, Romania, a former Axis member which had overthrown their pro-Axis government, was occupied by the Soviet Union as the sole representative of the Allies. After mass demonstrations by communist sympathisers and political pressure from the Soviet representative of the Allied Control Commission, a new pro-Soviet government that included members of the previously outlawed Romanian Workers' Party was installed. Gradually, more members of the Workers' Party and communist-aligned parties gained control of the administration and pre-war political leaders were steadily eliminated from political life. In December 1947, King Michael I was forced to abdicate and the People's Republic of Romania was declared.

Control over society became stricter and stricter, with an East German-style phone bugging system installed, and with the Securitate recruiting more agents, extending censorship and keeping tabs and records on a large segment of the population. By 1989, according to CNSAS, one in three Romanians was an informant for the Securitate. Ceaușescu also started becoming the subject of a vast personality cult, his portrait on every street and hanging in every public building.

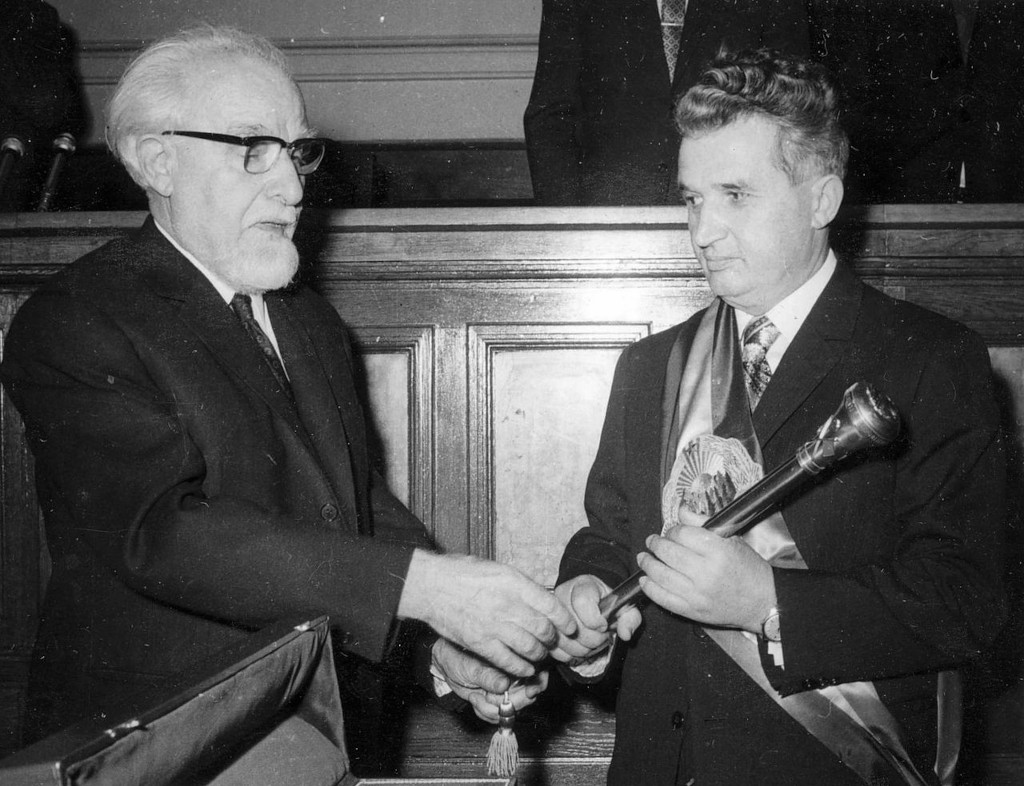

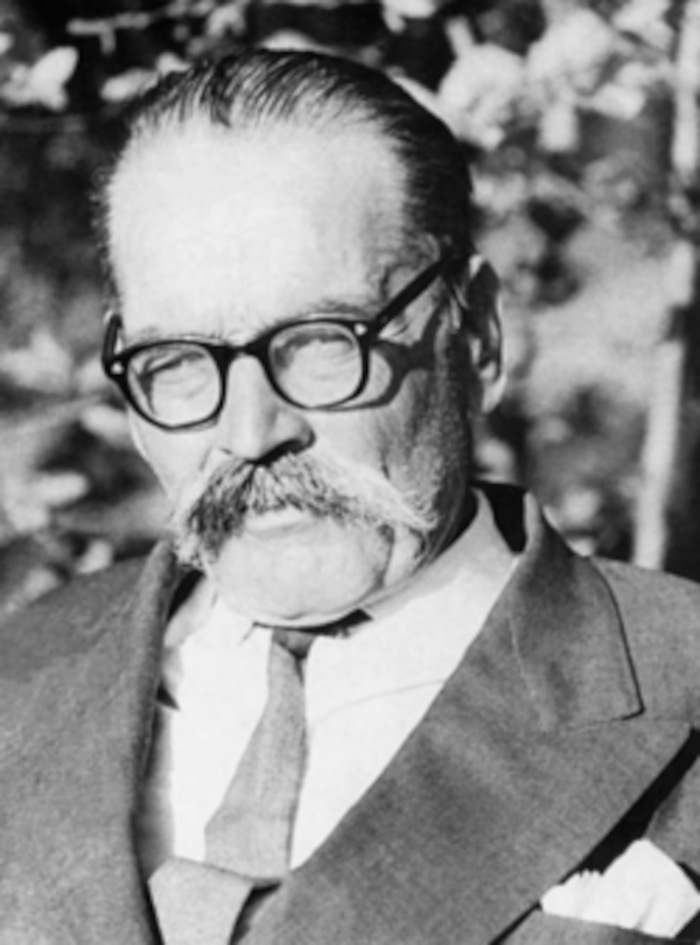

Nicolae Ceaușescu was the second and last communist leader of Romania, serving as the general secretary of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 to 1989. Widely classified as a dictator, he was the country's head of state from 1967 to 1989, serving as President of the State Council from 1967 and as the first President of the Republic from 1974. He was overthrown and executed in the Romanian Revolution in December 1989 along with his wife Elena Ceaușescu, as part of a series of anti-communist uprisings in Eastern Europe that year. Ceaușescu was a member of the Romanian Communist youth movement. Upon achieving power, Ceaușescu eased press censorship however, this period of stability was brief, as his government soon became totalitarian and came to be considered the most repressive in the Eastern Bloc.

His secret police, the Securitate, was responsible for mass surveillance as well as severe repression and human rights abuses within the country, and controlled the media and press. Ceaușescu's attempts to implement policies that would lead to a significant growth of the population led to a growing number of illegal abortions and increased the number of orphans in state institutions. His cult of personality experienced unprecedented elevation, followed by the deterioration of foreign relations, even with the Soviet Union. As anti-government protesters demonstrated in Timișoara in December 1989, Ceaușescu perceived the demonstrations as a political threat and ordered military forces to open fire on 17 December, causing many deaths and injuries. The revelation that Ceaușescu was responsible resulted in a massive spread of rioting and civil unrest across the country.

Ceaușescu and his wife Elena fled the capital in a helicopter enrouting to Vatican via Vienna, Austria, but they were captured in Romanian territory by the military after the armed forces defected. After being tried and convicted of economic sabotage and genocide, both were sentenced to death, and they were immediately executed by firing squad.

Ceaușescu created a pervasive personality cult, giving himself such titles as "Conducător" ("Leader") and "Geniul din Carpați" ("The Genius of the Carpathians"), with inspiration from Proletarian Culture (Proletkult). After his election as President of Romania, he even had a "presidential sceptre" created for himself, thus appropriating a royal insignia. This excess prompted painter Salvador Dalí to send a congratulatory telegram to the Romanian president, in which he sarcastically congratulated Ceaușescu on his "introducing the presidential sceptre". The Communist Party daily Scînteia published the message, unaware that it was a work of satire. The most important day of the year during Ceaușescu's rule was his official birthday, 26 January—a day which saw Romanian media saturated with praise for him. According to historian Victor Sebestyen, it was one of the few days of the year when the average Romanian put on a happy face, since appearing miserable on this day was too risky to contemplate. To execute a massive redevelopment project during the rule of Nicolae Ceaușescu, the government conducted extensive demolition of churches and many other historic structures in Romania. According to Alexandru Budistenu, former chief architect of Bucharest:

The sight of a church bothered Ceaușescu. It didn't matter if they demolished or moved it, as long as it was no longer in sight.

To lessen the chance of further treason after Pacepa's defection, Ceaușescu also invested his wife Elena and other members of his family with important positions in the government. This led Romanians to joke that Ceaușescu was creating "socialism in one family", a pun on "socialism in one country". Ceaușescu was greatly concerned about his public image. For years, nearly all official photographs of him showed him in his late 40s. Romanian state television was under strict orders to portray him in the best possible light. Additionally, producers had to take great care to make sure that Ceaușescu's height (he was only 1.68 metres (5 ft 6 in) tall) was never emphasised on screen. Consequences for breaking these rules were severe; one producer showed footage of Ceaușescu blinking and stuttering, and was banned for three months. As part of a propaganda ploy arranged by the Ceaușescus through the consular cultural attachés of Romanian embassies, they managed to receive orders and titles from numerous states and institutions. France granted Nicolae Ceaușescu the Legion of Honour. In 1978 he became a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB) in the UK.

Orphanhood in Romania became prevalent as a consequence of the Socialist Republic of Romania's natalist policy under Nicolae Ceaușescu. Its effectiveness led to an increase in birth rates at the expense of adequate family planning and reproductive rights. Its consequences were most felt with the collapse of the regime's social safety net during the 1980's Romanian austerity period, which led to widespread institutional neglect of the needs of orphans, with severe consequences in their health, including high rates of HIV infection in children, and well-being. Under Nicolae Ceaușescu, both abortion and contraception were forbidden. Ceaușescu believed that population growth would lead to economic growth. This increase in the number of births resulted in many children being abandoned in orphanages, which were also occupied by people with disabilities and mental illnesses. Together, these vulnerable groups were subjected to institutionalised neglect, physical and sexual abuse, and drug use to control behaviour. Though conditions in orphanages were not uniform, the worst conditions were mostly found in institutions for disabled children. One such example, the Siret children's psychiatric hospital, lacked both medicines and washing facilities, and physical and sexual abuse of children was reported to be common.

After the December 1989 Romanian Revolution, an initial period of economic and social insecurity followed. The 1990s was a difficult transition period, and it is during this period that the number of street children was very high. Some ran away or were thrown out of orphanages or abusive homes, and were often seen begging, inhaling 'aurolac' from sniffing bags, and roaming around the Bucharest Metro.

Because the staff had failed to put clothes on them, the children would spend their day naked and be left sitting in their own feces and urine. Nurses who worked at the institutions were not properly trained, and often abused the children. Dirty water was used for baths, and the children were thrown in three at a time by the staff. Due to the abuse children received from staff, older children learned to beat the younger ones. All children, including girls, had their heads shaved, which made it difficult to differentiate one another. Many had delayed cognitive development, and many did not know how to feed themselves. Physical needs were not met, as many children died of minor illness or injuries such as cataracts or anaemia. Many starved to death. Physical injuries that had to do with development included fractures that had not healed right, resulting in deformed limbs. Some children in the orphanages were infected with HIV/AIDS due to the practice of using unsterilised instruments. According to some sources, in 1989 there were approximately 100,000 children living in orphanages. Other sources put the figure at 170,000. Overall, it is estimated that about 500,000 children were raised in orphanages.

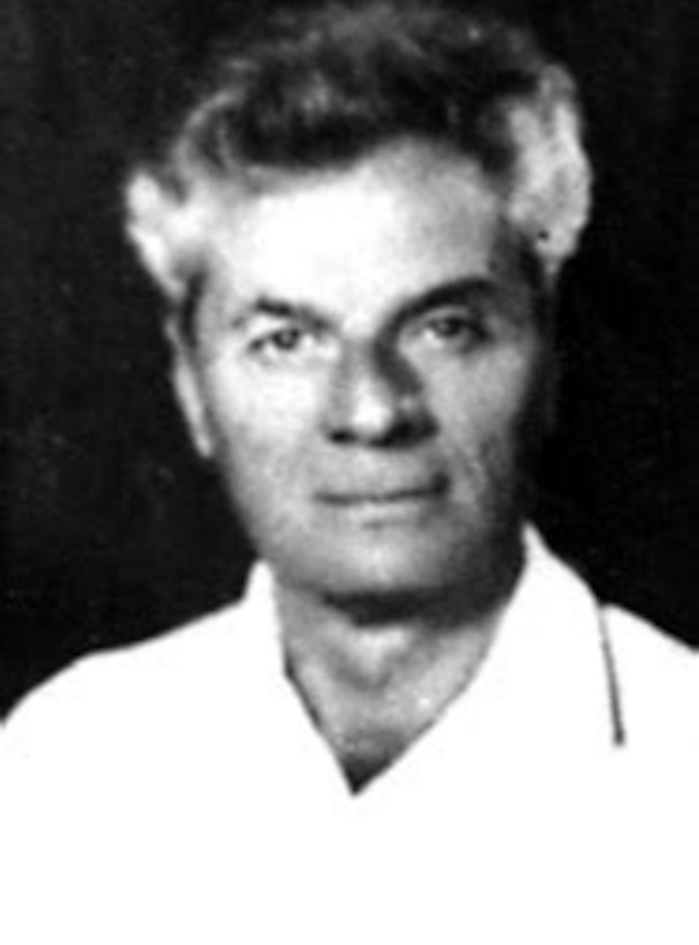

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej was the first Communist leader of Romania from 1947 to 1965, serving as first secretary of the Romanian Communist Party (ultimately "Romanian Workers' Party", PMR) from 1944 to 1954 and from 1955 to 1965, and as the first Communist Prime Minister of Romania from 1952 to 1955. Born in Bârlad (1901), Gheorghiu-Dej was involved in the communist movement's activities from the early 1930s. Upon the outbreak of World War II in Europe, he was imprisoned by Ion Antonescu's regime in the Târgu Jiu internment camp, and escaped only in August 1944. After the forces of King Michael ousted Antonescu and had him arrested for war crimes, Gheorghiu-Dej together with prime-minister Petru Groza pressured the King into abdicating in December 1947, marking the onset of out-and-out Communist rule in Romania.

Albanian Communist leader Enver Hoxha alleged that Gheorghiu-Dej personally pulled a gun on the King and threatened to kill him unless he gave up the throne. Hours later, Parliament, fully dominated by Communists and their allies after the elections held a year earlier, abolished the monarchy and declared Romania a People's Republic. From this moment onward, Gheorghiu-Dej was de facto the most powerful man in Romania.

Under his rule, Romania was considered one of the Soviet Union's most loyal satellite states, though Gheorghiu-Dej was partially unnerved by the rapid de-Stalinisation policy initiated by Nikita Khrushchev at the end of the 1950s. Gheorghiu-Dej stepped up measures that greatly increased trade relations between Romania and the Western countries. At the same time his government committed human rights violations within the country. He became general secretary in 1944 after the Soviet occupation, but did not consolidate his power until 1952, after he purged Ana Pauker and her Muscovite faction comrades from power. Ana Pauker had been the unofficial leader of the Party since the end of the war. Soviet influence in Romania under Joseph Stalin favored Gheorghiu-Dej, largely seen as a local leader with strong Marxist-Leninist principles.

Up until Stalin's death and even afterwards, Gheorghiu-Dej did not amend repressive policies, such as the works employing penal labor on the Danube-Black Sea Canal. On orders from Gheorghiu-Dej, Romania implemented also the massive forced collectivisation of land in the rural areas.

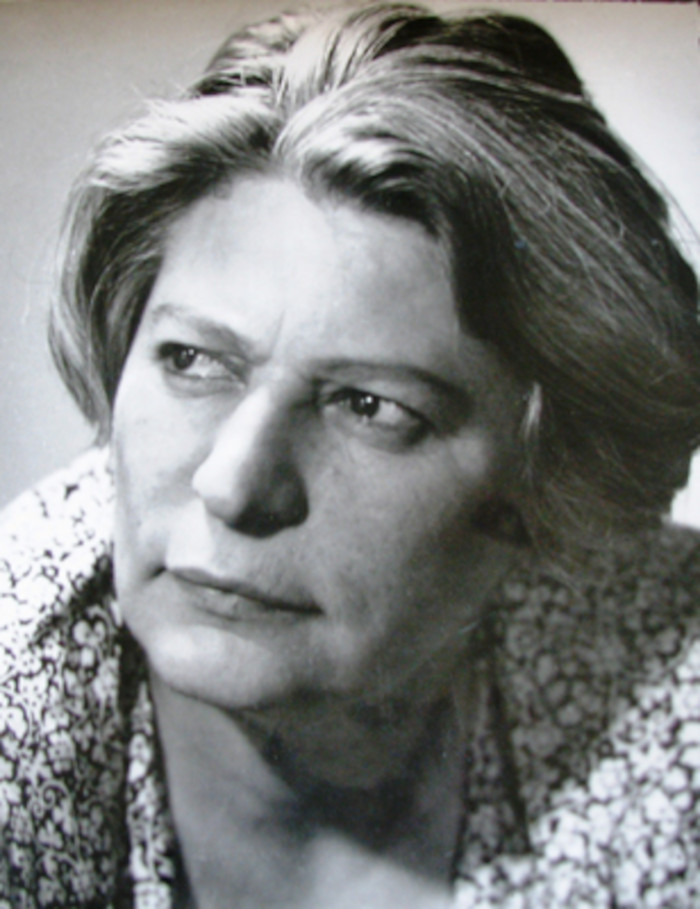

Ana Pauker (born Hannah Rabinsohn) was a Romanian communist leader and served as the country's foreign minister in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Ana Pauker became the world's first female foreign minister when entering office in December 1947. She was also the unofficial leader of the Romanian Communist Party immediately after World War II. Pauker was born into a poor, religious Orthodox Jewish family, her father was a traditional slaughterer and synagogue functionary, her mother a small-time food seller. As a young woman, Pauker became a teacher in a Jewish elementary school in Bucharest. While her younger brother was a Zionist and remained religious, she opted for Socialism, joining the Social Democratic Party of Romania in 1915 and then its successor, the Socialist Party of Romania, in 1918.

She was active in the pro-Bolshevik faction of the group, the one that took control after the Party's Congress of 8–12 May 1921 and joined the Comintern under the name of Socialist-Communist Party (future Communist Party of Romania). She and her husband, Marcel Pauker, became leading members. Pauker and her husband were arrested in 1923 and 1924 for their political activities and went into exile in Berlin, Paris, and Vienna in 1926 and 1927. In 1928, Pauker moved to Moscow to join the Comintern's International Lenin School, which trained senior Communist functionaries. In Moscow she became closely associated with Dmitry Manuilsky, the Kremlin's foremost representative at the Comintern in the 1930s.

Ana Pauker went to France, where she became an instructor for the Comintern being also involved in the communist movement elsewhere in the Balkans. Upon returning to Romania in 1935, she was arrested and shot in both legs when she tried to flee. Ana Pauker was the chief defendant in a widely publicised trial with other leading communists and was sentenced to ten years in prison. In May 1941, the Romanian government sent her into exile to the Soviet Union in exchange for Ion Codreanu. In the meantime, her husband had fallen victim to the Soviet Great Purge in 1938. Rumors abounded that she herself had denounced him as a Trotskyist traitor; Comintern archival documents reveal, however, that she repeatedly refused to do so. In Moscow, she became the leader of the Romanian communist exiles who later on became known as the "Muscovite faction".

She returned to Romania in 1944 when the Red Army entered the country, becoming a member of the post-war government, which came to be dominated by the communists. But it was her position in the Communist Party leadership that was paramount. Although she declined to become the General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party she formally held the number-two position in the Party leadership and was a member of the four-person Secretariat of the Central Committee. "Arguably the Jewish woman who achieved the most political power in the 20th century". Ana Pauker was widely believed to have been the actual leader of the Romanian communists in all but name during the immediate post-war period. she pursued what she later described as "Social Democratic policy" of mass recruitment of as many as 500,000 new Communist Party members without strict verification.

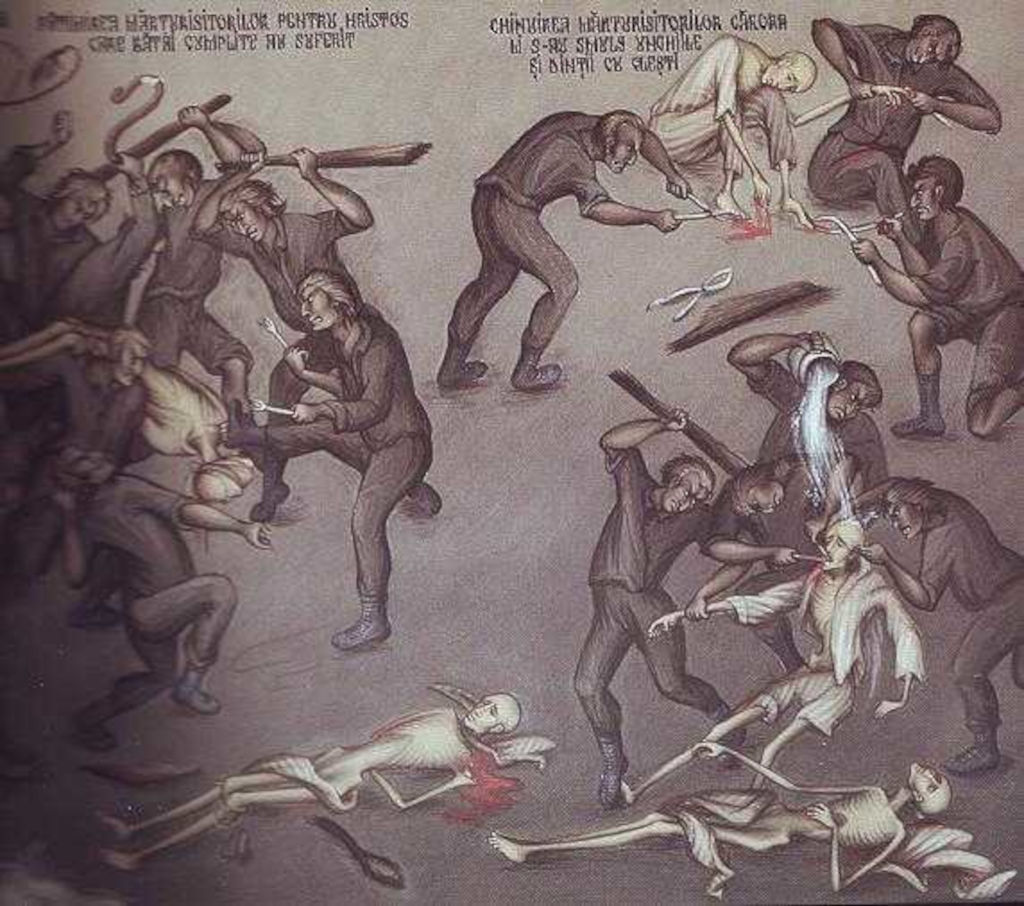

Re-education in Romanian communist prisons was a series of processes initiated after the establishment of the communist regime at the end of World War II that targeted people who were considered hostile to the Romanian Communist Party. The purpose of the process was the indoctrination of the hostile elements with the Marxist–Leninist ideology, that would lead to the crushing of any active or passive resistance movement. Reeducation was either non-violent – e.g., via communist propaganda – or violent, as it was done at the Pitești and Gherla prisons. Philosopher Mircea Stănescu claimed that the theoretical foundation for the communist version of the reeducation process was provided by the principles defined by Anton Semioniovici Makarenko, a Russian educator born in Ukraine in 1888.

Stănescu also asserted that another important factor was the definition of morality itself and that Lenin had reportedly stated any action that seeks the welfare of the party is considered moral, while any action that harms it is immoral. As such, moral itself is a relative concept, it follows the needs of the group. A certain attitude shall be regarded as moral at a given time, while immoral at another moment; in order to decide, the person must respect the program as defined by the collective (the party). After the installment of the communist regime, the prison system went through a transition period. Up to 1947, the detention regime was rather light, as the political prisoners were entitled to receive home packages, books, were granted access to discuss with family and even organise cultural events.

Gradually, the Securitate harshened the conditions, as the entire mechanism grew more solid. The old guards were replaced with new ones, adapted to the new society, the detention regime got rougher, beatings and torture during inquiry became common practice, together with mock trials.

The inquiries started there, at Suceava – as previously mentioned – in a hellish environment; you could not rest at night because of the beaten women screaming, inquired; the screams of those tortured, brought unconscious in the cell, livid, with shattered soles. It was infernal!.

At first, the main target during the investigation were members of the Iron Guard and of former historical parties. Later, they were joined by those who opposed collectivisation, who tried to illegally cross the border, members of resistance and, generally, opposers of the regime, even in nonviolent ways. Mircea Stănescu asserts that the communist regime did not consider imprisonment as a form of penitence, but a method of elimination from the social and political life, and, eventually, as a political reeducation environment.

Pitești Prison was a penal facility in Pitești, Romania, best remembered for the reeducation experiment (also known as Experimentul Pitești – the "Pitești Experiment" or Fenomenul Pitești – the "Pitești Phenomenon") which was carried out between December 1949 and September 1951, during Communist party rule. The experiment, which was implemented by a group of prisoners under the guidance of the prison administration, was designed as an attempt to violently "reeducate" the mostly young political prisoners, who were primarily supporters of the fascist Iron Guard, as well as Zionist members of the Romanian Jewish community.

After the purging of Romanian Communist Party leader Ana Pauker, the experiment was halted because the Romanian communist regime was sidelining its hardline Stalinist leaders. The overseers were put on trial; while twenty of the participating prisoners were sentenced to death, prison officials were given light sentences.

The Romanian People's Republic adhered to a doctrine of state atheism and the inmates who were held at Pitești Prison included religious believers, such as Christian seminarians. According to writer Romulus Rusan, the experiment's goal was to re-educate prisoners to discard past religious convictions and ideology, and, eventually, to alter their personalities to the point of absolute obedience. Estimates for the total number of people who passed through the experiment range from at least 780 to up to 1,000, to 2,000, to 5,000. Journalists Laurențiu Dologa and Laurențiu Ionescu estimate almost 200 inmates died at Pitești.

Journalist and anti-communist activist Virgil Ierunca referred to the "reeducation experiment" as the largest and most intensive brainwashing torture program in the Eastern Bloc. In even stronger terms, Nobel Laureate and Gulag survivor Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn called it "the most terrible act of barbarism in the contemporary world". Ex-detainee Gheorghe Boldur-Lățescu has described the Pitești Experiment as being "unique in the history of crimes against humanity". Located at the northern edge of Pitești, the building was structured on four levels: basement, ground floor, and two upper floors, arranged in a T-shaped design.

Inmates of Pitești Prison included:

Aristide Blank

Romanian financier, economist, arts patron and playwright. His father, Mauriciu Blank, an assimilated and naturalised Romanian Jew, was manager of the Marmorosch Blank Bank, a major financial enterprise.

Gheorghe Calciu-Dumitreasa

Romanian priest and dissident. In 1957 Calciu-Dumitreasa became one of the torturers in the "experiment" taking place in the Pitești Prison. In the mid-1980s he preached on the Voice of America and Radio Free Europe.

Ștefan Cârjan

Romanian football left winger and manager. After finishing his sentence, because of his refusal to collaborate with the Communist regime, Cârjan was forced to work for four years at the cutting of the common reed (Danube Delta).

Radu Ciuceanu

Romanian historian and politician. In 2010, the Bucharest Tribunal awarded him 600,000 Euros in damages for torture endured in communist prisons. Ciuceanu founded the National Institute for the Study of Totalitarianism.

Corneliu Coposu

Christian Democratic and liberal conservative Romanian politician, the founder of the Christian Democratic National Peasants' Party), the founder of the Romanian Democratic Convention and a political detainee.

Valeriu Gafencu

Arrested by the state authorities in 1941, he died 11 years later at Târgu Ocna Prison. Declared "Saint of the Prisons" by theologian Nicolae Steinhardt for his "exemplary Christian conduct and devotion to those in suffering".

Iuliu Hirțea

Romanian bishop of the Greek-Catholic Church. Released in July 1964 his health weakened by interrogations and torture and suffering from tuberculosis. Communist regime outlawed the Greek-Catholic Church.

Ion Ioanid

Romanian dissident and writer. Ioanid was a political prisoner who spent 12 years in prison and labor camps. He is best known for his book "Give us each day our daily prison", a reference to the Christian Lord's Prayer verse.

Nicolae Mărgineanu

Romanian psychologist. In his publications, he incorporated concepts from philosophy, literature, science and logic. A key work, Psihologia persoanei (1940), focuses on the uniqueness of the individual and his development.

Petre Pandrea

Romanian social philosopher, lawyer, and political activist, also noted as an essayist, journalist, and memoirist. Political opinions fluctuated between extremes—from right-wing conservatism to Marxism-Leninism.

Elisabeta Rizea

Romanian anti-communist partisan, she became the symbol of Romania's anti-communist resistance. Twice imprisoned for her activities, suffering extensive torture on the 2nd occasion. Rizea died in 2003 of viral pneumonia.

Virgil Solomon

Romanian physician and politician. With no arrest warrant to his name until 1954 and without trial, Solomon was held from 1947 to 1955 as a political prisoner. Vasile Luca, was heard saying that "Solomon must be immobilised".

When these wretched Communists came to power, they took everything from us, the land, the wooden carts — the hair off our heads. Still, what they could not take was our soul..

Alexandru Todea

Romanian Greek-Catholic bishop of the Alba Iulia Diocese and later cardinal. He was also a victim of the communist regime, suffering at Jilava, Sighet, and Pitești prisons. Todea is buried at the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Blaj.

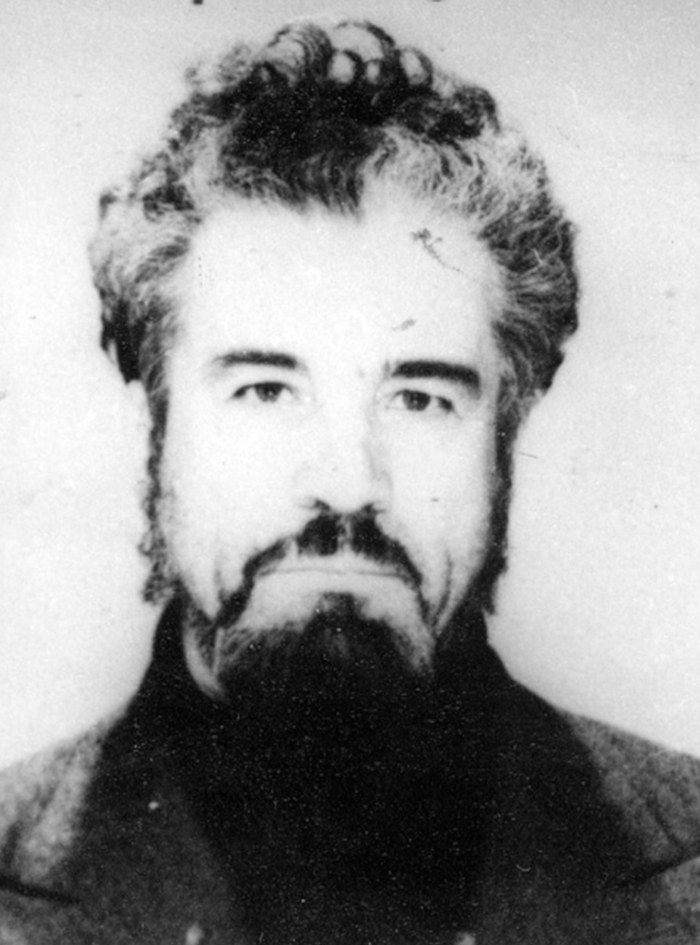

Eugen Țurcanu

Romanian criminal who led a group that terrorised their fellow inmates during the late 1940's at Pitești Prison in Pitești, Romania. Turcanu was a local communist official studying for a career in diplomacy.

Abraham Leib Zissu

Romanian writer, political essayist, industrialist, and spokesman of the Jewish Romanian community. Of modest social origin and a recipient of Hasidic education, a cultural activist, polemicist, and newspaper founder.

One of his victims later remembered Eugen Țurcanu as:

...a handsome man, out of the ordinary...with brown hair tending toward blond...when he frowned, you were terrified...his well-proportioned body seemed that of a performance athlete. When he punched or slapped you, he knocked you to the ground. When he got mad he was so crude that he destroyed everything in his path, like a ferocious killer. Moreover, he was unusually intelligent and had an extraordinary memory... but he was so Satanized you didn't know what to think of him....

During a June 1954 interrogation, Eugen Țurcanu described some of the torture methods he used at Pitești Prison: beatings:

On the soles of the feet, on the buttocks, on the back muscles of the legs, on the palms, over the face with the palms and the strap, over the face and under the sternum, choking the throat by hand. The beating was applied for about 10 minutes, which was repeated if necessary.Other methods includedrubbing the cement floor for 1 to 2 hours, standing for half a day, hitting the head against the wall..

The first political prisoners it housed arrived in 1942; these were high school students suspected of having taken part in the Legionnaires' rebellion. For a while after the proclamation of the Romanian People's Republic in December 1947, it continued to house primarily those found guilty of misdemeanors. Shortly after the establishment of the Securitate in August 1948, the Pitești Prison became a detention center for university students. By April 1949, the director of Pitești Prison was Alexandru Dumitrescu. According to Rusan, early attempts at "reeducation" had occurred at the prison in Suceava, continuing in a violent manner in Pitești and, less violently, at the Gherla Prison.

The group of overseers had been formed from people who had themselves been arrested and found guilty of political crimes. Their leader, Eugen Țurcanu, a prisoner and former member of the Iron Guard, who had also shortly joined the Communist Party before being purged, dissatisfied with the progress in Suceava, proposed using violent means in order to enhance the process, obtaining the agreement of the Pitești prison administration.

Guards would force them to attend scheduled or ad-hoc political instruction sessions, on topics such as dialectical materialism and Joseph Stalin's History of the CPSU(B) Short Course, usually accompanied by random violence and encouraged delation (demascare, lit. "unmasking") for various real or invented misdemeanors..

According to writers Ruxandra Cesereanu and Romulus Rusan the process begun in 1949 involved psychological punishment and physical torture. Initially the director of the prison, Dumitrescu, was not in favor of reeducation; he changed course, however, after Ion Marina, the local representative of the Securitate, applied pressure on him. Marina was closely coordinating with the leadership of the Directorate for Penitentiaries, particularly with Iosif Nemeș, the chief of the Operations Service, and with Tudor Sepeanu, the head of Inspection Services. Detainees, who were subject to regular and severe beatings, were required to engage in torturing each other, with the goal of discouraging past loyalties.

The process of re-education involved three stages:

- Each subject of the experiment was initially thoroughly interrogated, with torture applied as a mean to expose intimate details of his life ("external unmasking"). Hence, they were required to reveal everything they were thought to have hidden from previous interrogations; hoping to escape torture, many prisoners would confess to imaginary misdeeds.

- The second phase, "internal unmasking," required the tortured to reveal the names of those who had behaved less brutally or with relative indulgence to them in detention.

- Public humiliation was also enforced, usually at the third stage ("public moral unmasking"), inmates were forced to denounce all their personal beliefs, loyalties, and values. Notably, religious inmates had to blaspheme religious symbols and sacred texts.

According to Virgil Ierunca (an anti-communist activist and member of the Presidential Commission for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship in Romania), Christian baptism was gruesomely mocked. Guards chanted baptismal rites as buckets of urine and fecal matter were brought to inmates. The inmate's head was pushed into the raw sewage; their head would remain submerged almost to the point of death. The head was then raised, the inmate allowed to breathe, only to have his or her head pushed back into the sewage. Ierunca further states that the prisoners' whole bodies were burned with cigarettes; their buttocks would begin to rot, and their skin fell off as though they suffered from leprosy. Others were forced to swallow spoons of excrement, and when they threw it back up, they were forced to eat their own vomit.

The inmates were required to accept the notion that their own family members had various criminal and grotesque features; they were required to author false autobiographies, comprising accounts of deviant behavior. Any prisoner who refused to become a perpetrator or who did not beat a former friend mercilessly was crushed by Țurcanu’s most brutal assistants — Steiner, Gherman, Pătrășcanu, Roșca, and Oprea. In addition to physical violence, inmates subject to "reeducation" were supposed to work for exhausting periods doing humiliating chores – for instance, cleaning the floor with a rag clenched between the teeth. Inmates were malnourished and kept in degrading and unsanitary conditions.

Not able to resist the physical and psychological violence, some prisoners tried to commit suicide by severing their veins. Two of the inmates, Gheorghe Șerban and Gheorghe Vătășoiu, ended their lives by throwing themselves through the opening between the stairways, before safety nets were installed. Many died from injuries sustained during beatings and torture. Alexandru Bogdanovici, one of the initiators of the reeducation process at Suceava, was repeatedly tortured until his death in April 1950. Historian Adrian Cioroianu argued that techniques used by the ODCC could have been ultimately derived from Anton Makarenko's controversial pedagogy and penology principles in respect to rehabilitation.

In 1952, as Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej successfully maneuvered against the Minister of the Interior Teohari Georgescu, the process was stopped by the authorities themselves. The ODCC secretly faced trial for abuse, and over twenty death sentences were handed out on 10 November 1954. Țurcanu was held responsible for the murder of 30 prisoners, and the abuse exercised on 780 others. He and sixteen accomplices were executed by firing squad on 17 December at Jilava Prison. Securitate officials who had overseen the experiment were tried the following year; all were given light sentences, and were freed soon after. Colonel Sepeanu was arrested in March 1953 and sentenced to 8 years on 16 April 1957, but was pardoned and set free on 13 November of that year.

Responding to new ideological guidelines, the court concluded that the experiment had been the result of successful infiltration by American and Horia Sima's Iron Guard agents into the Securitate, with the goal of discrediting Romanian law enforcement.

Gherla Prison is a penitentiary located in the Romanian city of Gherla, in Cluj County. The prison dates from 1785; it is infamous for the treatment of its political inmates, especially during the Communist regime. In Romanian slang, the generic word for a prison is "gherlă", after the institution. From late summer 1944 until early 1945, the prison was used as a deposit for the Soviet Army. It housed both political prisoners and common criminals from 1945, all men. Between 1945 and 1964, many inmates were peasants and workers, while others came from the middle class: self-employed, intellectuals, pupils and students. Many anti-communist resistance figures spent jail time or disappeared forever into this prison.

The spacious building soon filled up, with eight to twelve crowded into two-man cells. There were 703 prisoners in late 1948, of whom over 600 were political. By 1950, there were 1600, almost 1200 of them political. The population peaked at 4500 in summer 1959, dropping to 600 by 1964. According to a study done by the International Centre for Studies into Communism, 20.3% of all political prisoners in Communist Romania spent time at Gherla. Food consisted of gruel and sour soups, consumed in a foul air, and packages were forbidden from 1951. Beatings and torture made it among the toughest prisons in the system. The prison (called by the locals the "Yellow House") was very imposing. To the south was a cemetery, and next to it, a smaller one, for detainees dying at the prison.

In June 1950, a group of torturers arrived at Gherla from Pitești, the site of a wide-ranging experiment in “re-education”. Led by Alexandru Popa Țanu, they were joined in December by another group from Târgșor, where the experiment had failed. In August 1951, Eugen Țurcanu, the lead torturer at Pitești, arrived at Gherla. During the preceding fourteen months, Țanu, his adjunct and rival at Pitești, had won the respect of the Gherla administration. As a result, in trying to mark their territory, the two men exacerbated the beatings and tortures, doubling the number of deaths in Room 99, nicknamed the “chamber of death”. The prison doctor falsified the death certificates of those who had succumbed to torture, eventually serving five years in prison.

Room 99, isolated from the other cells, was very spacious; prisoners would sit around the edges, with the torturers guarding the exits. Whoever complained to the guards would immediately be beaten, stripped naked, chained to the solitary confinement cell, constantly having cold water poured on him and left to hunger for days on end. Room 97 had wooden beds, with detainees staying naked underneath. Known as the “madmen’s room”, it involved savage beatings to the point of unconsciousness. Room 97, the “Chinese cell”, involved tying down the victim and subjecting him to a form of Chinese water torture.

By late 1951, “re-education” had failed in several prisons and was fading away in Pitești. That December, Țurcanu and ten associates, believing they were on the way to Aiud in order to continue the process there, were in fact transported to Jilava for interrogation. Two torturers carried on at Gherla until March 1952, either because the Securitate secret police wanted to carry on the experiment under maximum-security conditions, or because they wished to collect evidence for the eventual trial of the Țurcanu group. With the end of "re-education" came a new warden, the notorious Petrache Goiciu, who quickly turned the prison into a place of hard work and violence. The remaining "re-educators" assumed a position as prominent torturers, who ended up killing Ioan Flueraș.

Inmates of Gherla Prison included:

Alexandru Zub

Romanian historian, biographer, essayist, political activist and academic. A former professor at the University of Iași, noted for his contribution to the study of cultural history and Romanian history.

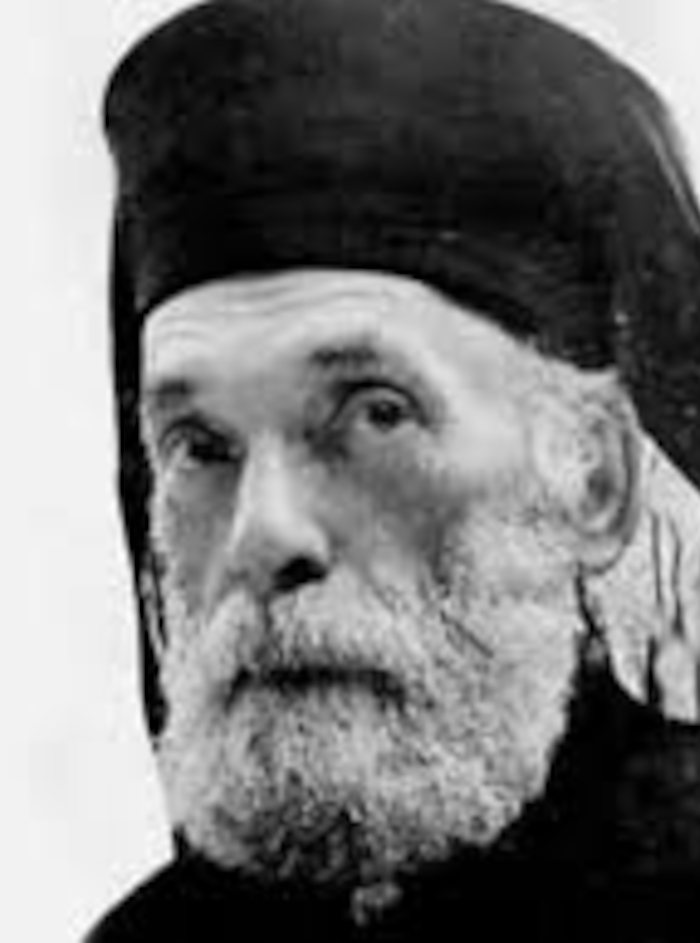

Richard Wurmbrand

Romanian Evangelical Lutheran priest, and professor of Jewish descent. In 1948, having become a Christian ten years before, he publicly said Communism and Christianity were incompatible.

Ștefana Velisar Teodoreanu

Romanian novelist, poet and translator, wife of the writer Ionel Teodoreanu. An anti-communist like her husband, Velisar helped writers and political figures persecuted by the communist regime.

During Wurmbrand's imprisonment, he was beaten and tortured. He stated that his physical torture included mutilation, burning and being locked in a large frozen icebox. His body bore the scars of physical torture for the rest of his life. For example, he later recounted having the soles of his feet beaten until the flesh was torn off, then the next day beaten again to the bone, claiming there were not words to describe that pain. Wurmbrand travelled to Norway, England, and then the United States becoming known as "The Voice of the Underground Church", doing much to publicise the persecution of Christians in Communist countries. He compiled circumstantial evidence that Karl Marx was a Satanist.

Păstorel Teodoreanu

Romanian humorist, poet and gastronome, opinionated columnist, famous wine-drinking bohemian, and decorated war hero. Worked with the influential literary magazines of the 1920s.

Nicolae Steinhardt

Romanian writer, Orthodox monk and lawyer. His main book, Jurnalul Fericirii, is regarded as a major text of 20th-century Romanian literature and a prime example of Eastern European anti-Communist literature.

Ion Dezideriu Sîrbu

Romanian philosopher, novelist, essayist, and dramatist. An academic and theater critic, sentenced without trial under the charge of "conspiring against the regime", spending fourteeen years as a political prisoner.

One night shortly thereafter, he was moved into a ground-floor cell, where three ex-"re-educators" beat him until morning with their fists, broomsticks, boots and sandbags. Sent to the sickroom, the doctor ignored him and only an assistant wiped and tried to feed Flueraș, who died. The killing had been ordered from the top echelons of the ministry. Gherla was associated with summary, extralegal executions. In 1950, a convoy of 38 detainees left the prison and its members were shot. From 1958 to 1960, twenty-eight judicial executions were carried out at the prison; 200 prisoners died during the same period.

In 1958, the Hunedoara Securitate concocted a plan for eliminating opponents of collectivisation or of the regime. It invented a resistance group called the White Guard. Ioan Nistor, a technician at the Hunedoara Steel Works, was selected as leader. Another 72 people, many of whom were strangers to one another, were arrested. Nistor was tried and executed at Gherla in January 1959. Another eight executions of the fictitious group’s members took place there in 1958–1959. In June 1958 a group of prisoners—consisting mostly of young men who had tried to escape to Yugoslavia, and had either been caught or returned to Romania—rebelled, asking for a more humane treatment. The disturbance was quickly put down by the authorities, and the rebellious inmates were subjected to terrible beatings and torture; twenty-two of them received sentences of five to fifteen years.

In an interview with Adevărul, an ex-detainee, Constantin Vlasie, recounts how the guards at Gherla Prison "were evil. They made us eat feces, we slept on the floor, they beat our feet until we fainted." He went on: "They wanted to break up our morale. They had evil methods to make us renounce our faith and worship them instead." Another ex-prisoner, Mihai Stăuceanu (arrested for being a border-jumper), recalls: "The detention regime at Gherla was probably very similar to the extermination regime applied in the NAZI camps: 10 to 12 hours of physical work on a construction site, which was cordoned off with double fences of barbed-wire and with guarding towers, exactly like those to be found at the border." From 1964 to 1989, the prison housed common criminals.

Together with the prisons at Sighet, Gherla, and Râmnicu Sărat, the Aiud penitentiary was the most important and the harshest place of detention for political prisoners in Communist Romania. Political prisoners were detained at this facility from 1945 all the way up to the Romanian Revolution of 1989. In 1945 there were only 164 inmates left at Aiud; by the end of 1946 there were 345 inmates condemned of political crimes and 93 accused of such crimes. Those numbers increased in 1947 to 256 and 346, and in 1948 to 889 and 1,269, respectively. Overall, in the first 4 years after the war, authorities incarcerated at Aiud Prison 2,405 condemned individuals and 1,683 indicted individuals. A CIA report from January 1954 observes: "Aiud Prison is one of the largest and harshest in Rumania. No letters or packages from home are allowed political prisoners, except that they are occasionally allowed to write home for winter clothing. [...] Punishment consists of confinement in the "reserve," a box almost without air; forced labor; or labor on the famous Danube–Black Sea Canal.".

In his memoirs, Give us each day our daily prison, Ion Ioanid recounts the 12 years he spent in the prisons and labor camps of Communist Romania. He notes that Aiud's isolation from the outside world was the most severe, and states: "Its reputation was well established. The prison of all prisons. It became a symbol. The Holy of Holies.". From 1945 to 1948, the director of Aiud Prison was Alexandru Guțan; during his tenure, the first re-education program in Communist Romania took place there. According to his testimony (available in the archives of the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives), "work of political diversion that would lead to discord and crushing one another" was necessary. While Ștefan Koller was the prison's commandant, from 1953 to 1958, the conditions were extremely harsh, and over 100 detainees died. Most deaths at Aiud occurred from 1958 to 1964, when the notorious Securitate Colonel Gheorghe Crăciun was in charge.

Târgșor Prison is a prison complex in Târgșoru Nou, a component village of Ariceștii Rahtivani commune, Prahova County, located in central Muntenia, Romania. From 1948 to 1952, this was the only prison for children in the world (dubbed the "Prison of Angels"). The children were subjected to the cold and to beatings; they were hungry and isolated in cramped rooms, without light, with boarded-up windows, where ventilation was done through tiny cracks around the door frames and windows. Hundreds of recalcitrant minors (some as young as 12) were subjected to psychological experiments and beaten with the intention of being "re-educated" in the spirit of the "Communist new man". The re-education of minors was personally coordinated by Securitate major-general Alexandru Nicolschi, one of the main organisers of the Pitești Experiment; other Securitate officers involved were colonels Mișu Dulgheru and Ludovic Czeller. From summer 1948 to June 1949, over 800 children, mostly students, arrived at Târgșor.

One batch consisted of students from Dragoș Vodă High School in Sighetu Marmației, who were accused of demonstrating against the regime. By September 1949, some 870 former Romanian Police cadres, including old prison guards and members of the Siguranța statului (such as Constantin Maimuca, its deputy director in 1940–1941) had been rounded up and sent to Târgșor, where they maintained fervent (but unrealistic) beliefs about a coming American liberation of Romania. Another category of prisoners who were incarcerated at Târgșor were people detained by the Securitate after being accused of subversive revolutionary activities, such as Sorin Bottez and Radu Ciuceanu. In 1950, the prisoners were transferred to other penal institutions and Romanian prisoners from the Soviet Union were brought in their place. On January 6, 1952, all male prisoners were transferred to other penal institutions and female prisoners were brought in their place.

Sighet Prison located in the city of Sighetu Marmației, Maramureș County, Romania, was used by Romania to hold criminals, prisoners of war, and political prisoners. It is now the site of the Sighet Memorial Museum, part of the Memorial of the Victims of Communism. While Northern Transylvania was under Soviet military administration from November 1944 to March 1945, the building was used for interning Soviet deserters and delinquents, subsequently returned to the Soviet Union. After the end of World War II, ethnic German war prisoners passed through Sighet, some on their way to forced labor in the Soviet Union. Between 1947 and 1950, common criminals formed the majority of detainees. However, political prisoners began to appear: peasants from the surrounding Maramureș region who refused to hand over food quotas to the state. Among the earliest arrivals were eighteen pupils from Dragoș Vodă High School, accused of demonstrating against the new communist regime; they were incarcerated in August 1948 and kept until May 1949.

On the night of May 5/6, 1950, a Securitate secret police operation led to the arrest of some 80 high-ranking politicians from the 1918–1945 period, largely from the National Peasants' Party and the National Liberal Party. The operation involved 228 agents acting in 38 teams of six. After a brief stay at the Interior Ministry in Bucharest, they were taken to Sighet in vans, arriving on May 7. It is believed that the prison was chosen for its geographic isolation and proximity to the Soviet Union; in the event of an anti-communist revolt, the prisoners could be whisked across the border. On May 26, the group of Romanian Greek-Catholic bishops and priests arrested in October 1948, previously held at Dragoslavele and Căldărușani Monastery, arrived. Other imprisoned politicians and Greek-Catholic clerics arrived until 1952; detainees at Sighet numbered 89 by that August. Only the Maniu–Mihalache prisoners were at Sighet following a public trial, held in November 1947.