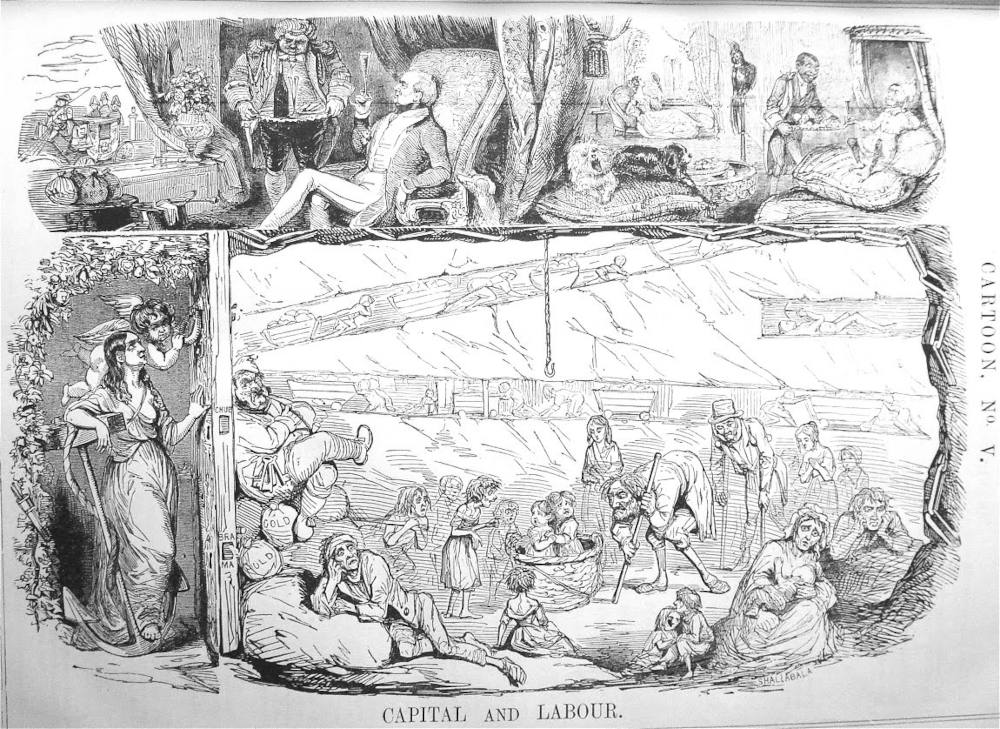

Displaced, subjugated, compartmentalised; threatened with banishment and interned by poverty into collectivised machination.

Workhouse

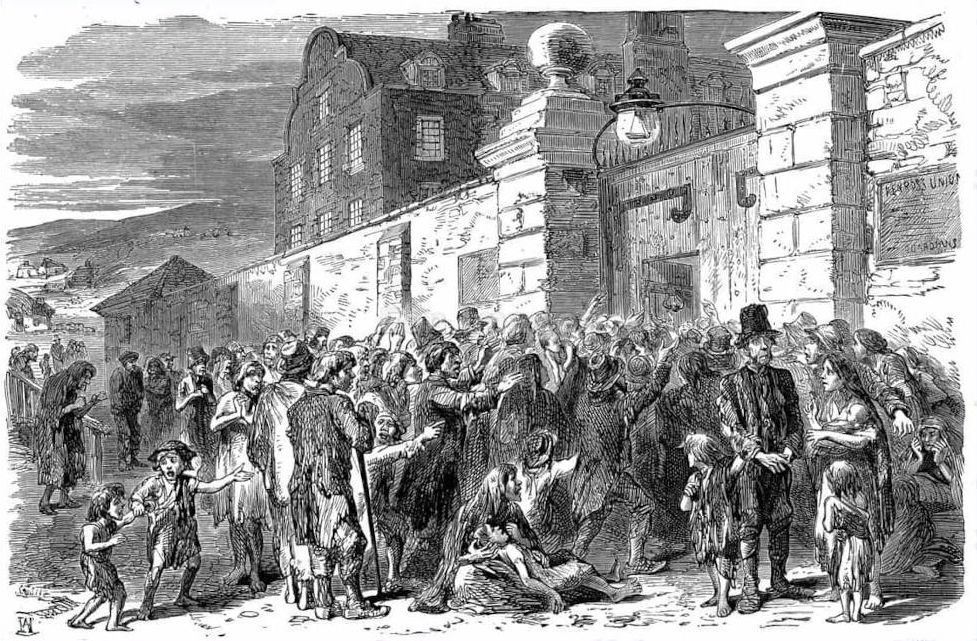

White Victorians who had not fled or had been banished from the United Kingdom, who had avoided Colonialisation were thus interned and marginalised into a gruelling collectivisation of misery, known as the Workhouse and later to others as Gulag. At its height the 19th century saw 700 workhouses housing 250,000 people with some, such as Lambeth in London, holding up to 1,000 people at a time.

The Vagrancy Act 1824 is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom that makes it an offence to sleep rough or beg. It remains in force in England and Wales, and anyone found to be sleeping in a public place or to be trying to beg for money can be arrested. Contemporary critics, including William Wilberforce, condemned the Act for being a catch-all offence because it did not consider the circumstances as to why an individual might be placed in such a predicament.

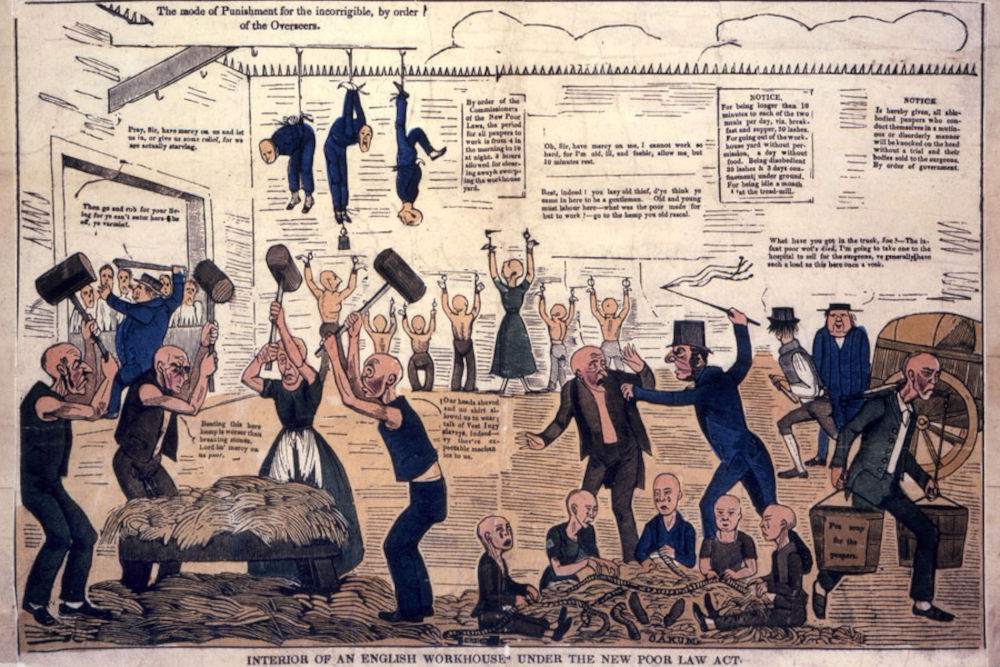

Vagrants refused entry to Workhouses risked being sentenced to two weeks of hard labour if they were found begging or sleeping in the open and prosecuted for an offence under the Vagrancy Act 1824.

The law was enacted to deal with the increasing numbers of homeless and penniless urban poor in England and Wales following the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. Nine years after the Battle of Waterloo, the British Army and British Navy had undergone a massive reduction in size, leaving large numbers of discharged military personnel without jobs or accommodation. At the same time, a massive influx of famished and displaced economic migrants from Ireland and Scotland arrived in England, especially London, in search of work.

The workhouse is an inconvenient building, with small windows, low rooms and dark staircases. It is surrounded by a high wall, that gives it the appearance of a prison, and prevents free circulation of air. There are 8 or 10 beds in each room, chiefly of flocks, and consequently retentive of all scents and very productive of vermin. The passages are in great want of whitewashing. No regular account is kept of births and deaths, but when smallpox, measles or malignant fevers make their appearance in the house, the mortality is very great. Of 131 inmates in the house, 60 are children.

The Great Reform Bill of 1832 saw an extension of the voting rights — but just to the Middle class. The Tories of the Duke of Wellington resisted this, fearing a collapse of law and order and an opening of the floodgates to the “scum of the earth”. The prime mover was the Prime Minister Earl Grey (yes, famous for the tea) — a man so afraid of the looming working-class population boom that him and his wife had 17 children. However, the older he got, the more nervous about what his very minor actions towards voter enfranchisement might have let loose, and so he handed over to a more cautious Whig — Viscount Melbourne, who oversaw the introduction of the new poor law.

Thomas “web-toe” Malthus

Known for views Malthusian trap and Malthusian catastrophe.

Melbournes main achievement was “Poor Law reform” — by which he meant “restricting the terms on which the poor were allowed relief and the establishment of compulsory admission to workhouses for the impoverished”.

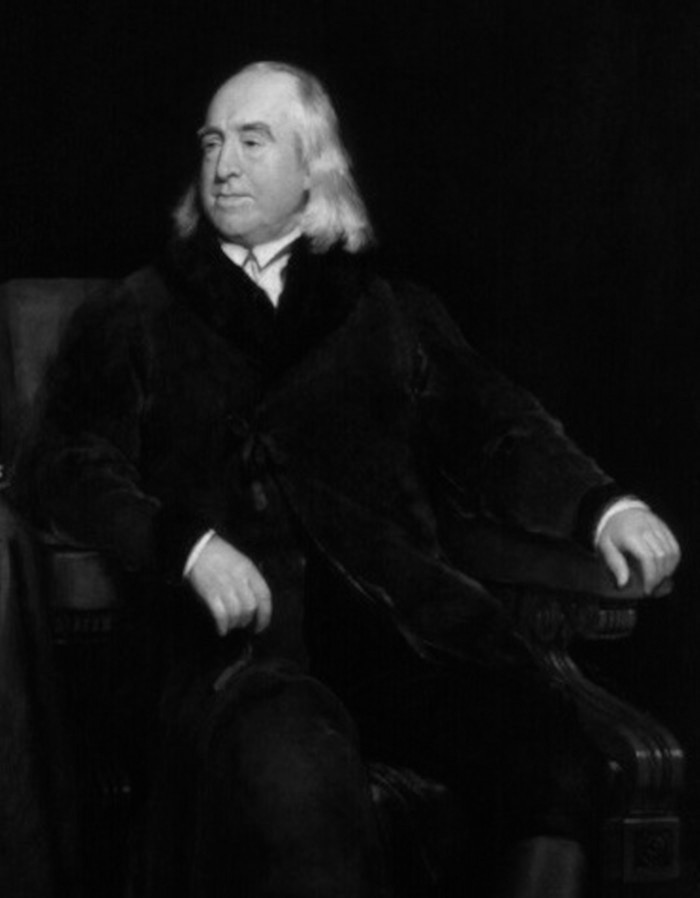

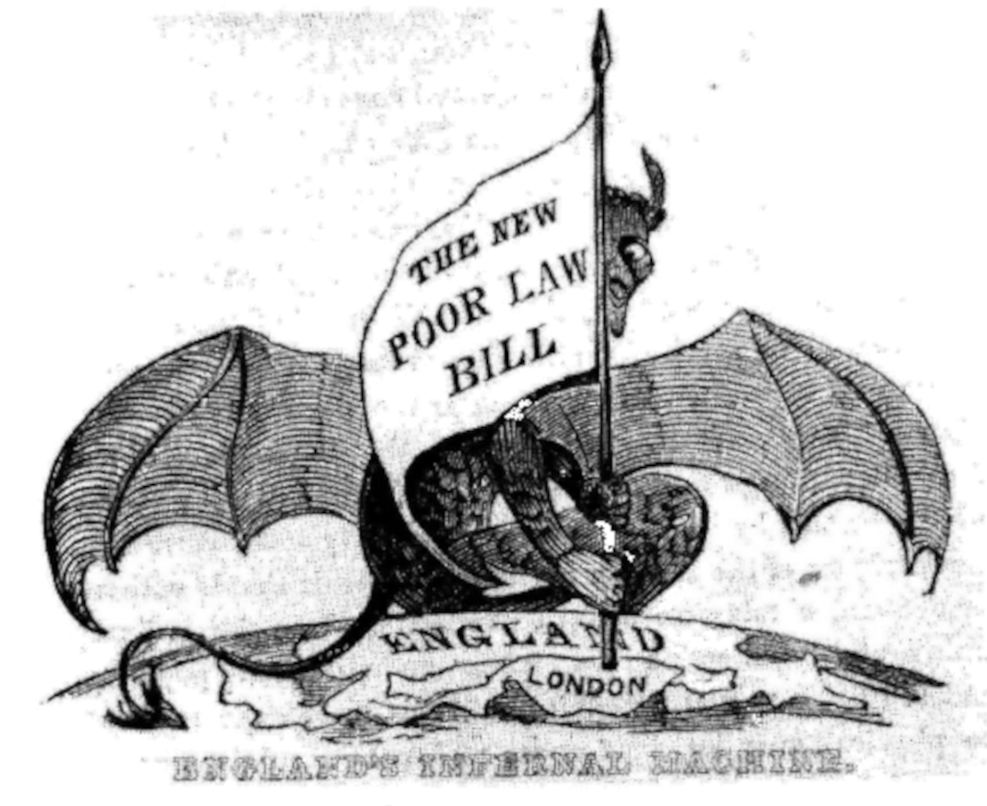

Whether it was Thomas Malthus (who Dickens satirised with his character Scrooge) and his dire warnings that “population was increasing faster than resources, so we better lock the poor up in workhouses” or Jeremy Bentham’s “the poor would rather do whatever they found pleasant rather than work, so we better lock them up in workhouses” the laws went through Parliament almost unopposed.

A small group of radicals were against Poor Law reform such as William Cobbett who believed the poor “…had an automatic right to relief” and “that the Act aimed to enrich the landowner at the expense of the poor” and John Fielden who saw no difference between Tory and Whig saying he would resist a law "based upon the false and wicked assertion that the labouring peoples of England were inclined to idleness and vice”.

The working class could not vote, but the 1830s also saw the dawning of the Trades Union movement, with the launch of the campaign around the Tolpuddle Martyrs in 1834 and the rise of the mass working-class Chartist movement, many meetings of which were chaired by John Fielden. In some places workhouses were attacked and Poor Law Guardians often had to be protected by Police and troops. Incidences included the Plug Riots in Stockport and the Rebecca Riots in Carmarthen.

The Anti-Poor Law movement emerged as soon as the New Poor Law of 1834 started enclosing paupers within newly built union workhouses. When paupers disappeared from the public gaze to be enclosed in newly built union workhouses and the poor rate fell by twenty percent in its first three years, the new system was perceived to be a success. Therefore, complaints about deliberate inadequacy of diets, excessive measures of discipline, separation of married couples and even removal of children from their parents were overlooked.

The implementation of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, and its accompanying nationwide system of union workhouses, were placed in the hands of the three Poor Law Commissioners known as "The Bashaws” based at Somerset House in London their secretary and nine clerks or assistant commissioners. James Kay-Shuttleworth, an Assistant Commissioner, believed that pauperism was caused by the "recklesness and improvidence of the native population [and the] barbarism of the Irish.”.

These poor law commissioners were:

- Sir Thomas Frankland Lewis 18 August 1834 – 30 January 1839

- John George Shaw Lefevre 18 August 1834 – 25 November 1841

- Sir George Nicholls 18 August 1834 – 17 December 1847

- Sir George Cornewall Lewis 30 January 1839 – 2 August 1847

- Sir Edmund Walker Head 25 November 1841 – 17 December 1847

- Edward Turner Boyd Twistleton 5 November 1845 – 23 July 1847

The Commissioners issued a continual stream of detailed regulations and order to the 600 or so Poor Law Unions in England and Wales. Some of these orders, known as Special Orders, applied only to specified unions and did not require parliamentary approval. Others, known as General Orders, applied to all unions and did require the endorsement of parliament.

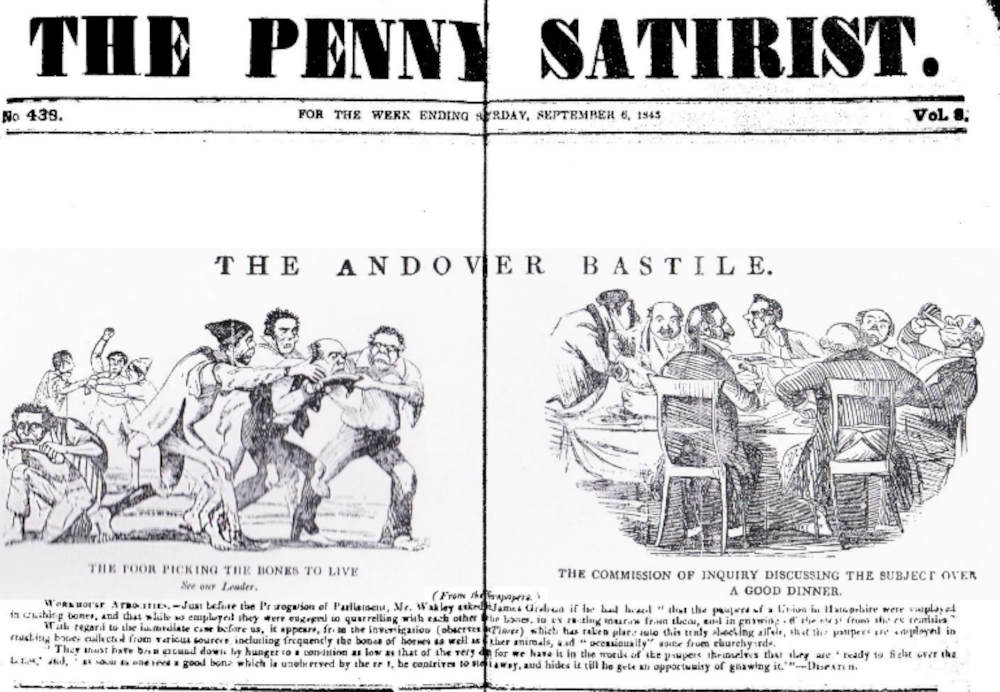

The commission lasted until 1847 when it was replaced by a Poor Law Board — the Andover workhouse scandal being one of the reasons for this change. During this year, after a decade of evolution, the General Orders in force at that time were brought together as the Consolidated General Order. This effectively became the 'bible' of poor-law and workhouse operation, and remained largely unchanged until a major updating took place in 1913.

Lifelong Stigmatism

Whether you admitted yourself or were born into a workhouse, it carried a stigma that would stay with you for the rest of your life. That stigma was so great that laws were changed in 1904 to help children born in a workhouse to escape the cloud that followed them. Before then, a birth certificate reflected the name of the workhouse into which a child was born. But after the laws were changed, new addresses were used instead.

Although that made it challenging to research an affected person’s family history, most workhouses used the same name on all birth certificates. For example, the Pontefract institution was listed as 1 Paradise Gardens in Tanshelf, Pontefract, Barton-upon-Irwell became known as 21 Green Lane in Patricroft, Eccles, and Bristol was listed as 100 Manor Road in Fishponds, Bristol.

Sometimes, the address corresponded to the actual address of the institution but not always. Liverpool was recorded as 144A Brownlow Hill, even though that address didn’t exist. In some cases, when the street address referred to “workhouse,” the address was changed to eliminate it. By 1918, the same thing was done to death certificates because the stigma of dying in a workhouse also followed a family. In 1921, Scotland changed their laws as well.

Child Abuse

Children were among the primary targets for cold, uncaring workhouse personnel. In 1894, 54-year-old Ella Gillespie, a former nurse and overseer at Hackney Union’s Brentwood schools, stood trial on charges of neglect and abuse of the children in her care. For approximately eight years, Gillespie was in charge of about 500 children. As those children came forward to testify against her, the entire country was horrified by the scandal. Punishments and abuses were severe, bordering on bizarre. A common punishment was the “basket drill,” where children in nightclothes paraded around their rooms for hours while balancing their daytime clothes in baskets on their heads.

Talking to other children was punishable by having their heads slammed against the wall. There were also spur-of-the-moment blows with hands or frying pans. Children were often sent to fetch stinging nettles before being beaten with them. In addition, water was often withheld, forcing children to drink from puddles outside or toilets inside. Others testified that Gillespie was regularly drunk, avoiding detection of her crimes during surprise inspections by meeting inspectors outside the school and treating them to lunch first. Gillespie was found guilty, receiving five years’ penal servitude as her punishment.

Mind control and Subordination

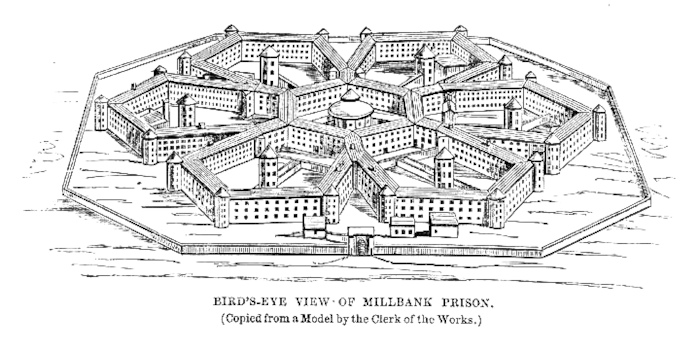

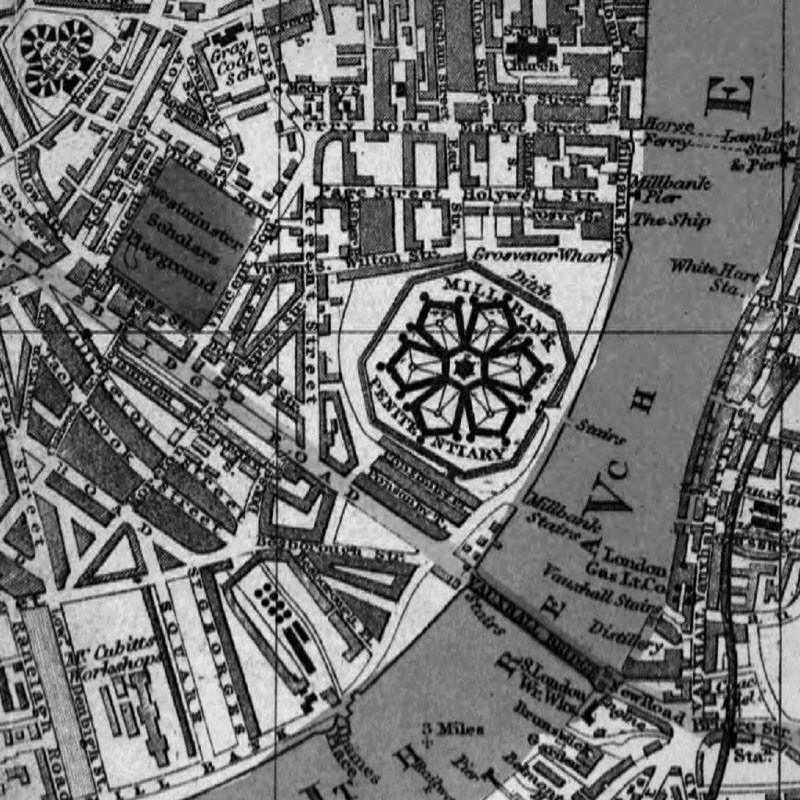

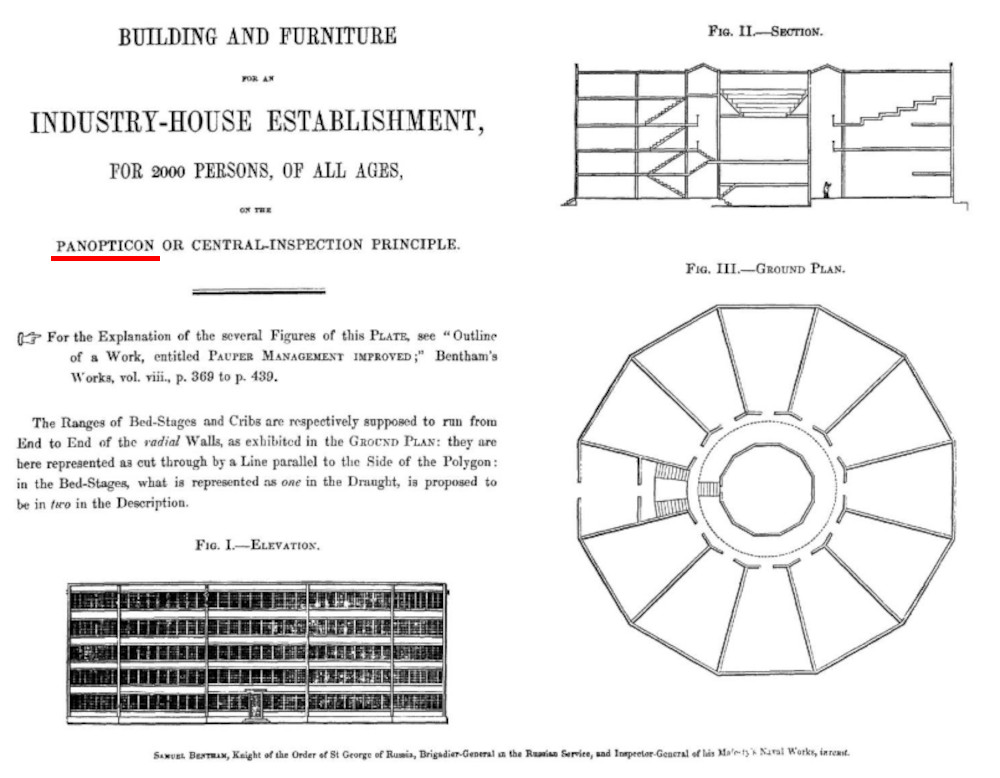

In the introductory paragraph of his initial panopticon description, Bentham already made clear, that this was not a device solely for carceral reform, but it was also designed to deal with the problem of pauperism. “By a simple idea in Architecture,” he proclaimed, referencing his panoptic institution, “the gordian knot of the Poor Laws are not cut, but untied.” Described by Bentham as “a mill for grinding rogues honest and idle men industrious,” the new panoptic institution was about to form the ideological and architectural structure of the new union workhouse apparatus.

In his later work titled Pauper Management Improved (1798), Bentham elaborated how the new workhouse system should function, and suggested” the whole body of the burdensome poor to be maintained and employed, in a system of Industry-houses, upon a large-scale, distributed over the face of the country as equally as may be” (italic words are Bentham’s original emphasis).

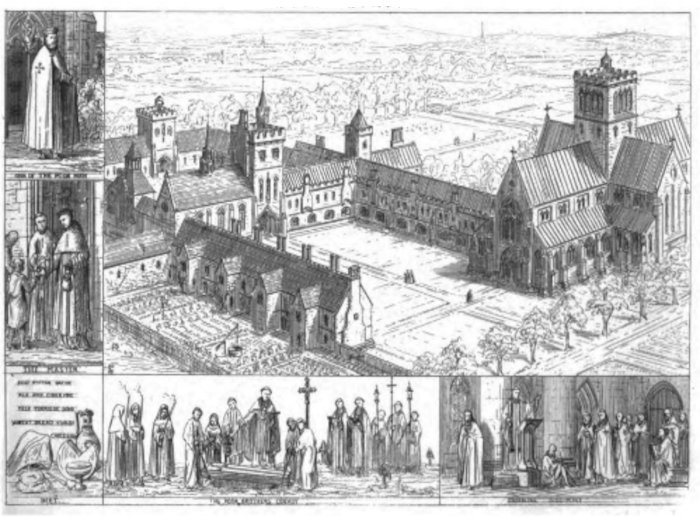

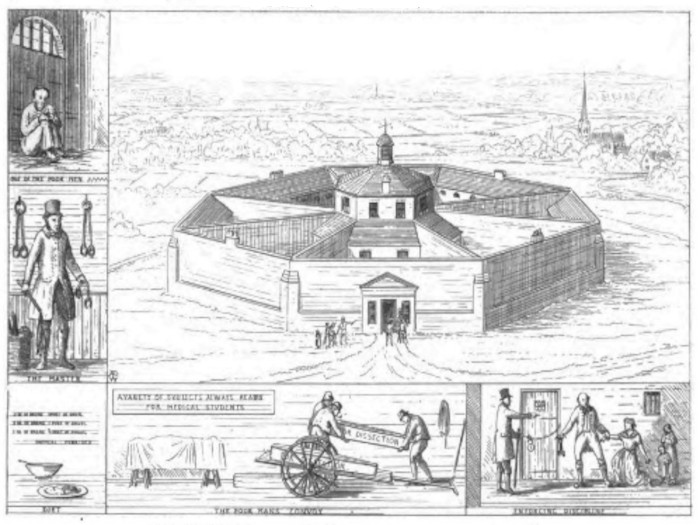

Contrasted Residences for the Poor in Pugin’s Contrasts [From Pugin’s Contrasts (1841)]

Bentham was a determined opponent of religion, as Crimmins observes:

Between 1809 and 1823 Jeremy Bentham carried out an exhaustive examination of religion with the declared aim of extirpating religious beliefs, even the idea of religion itself, from the minds of men.

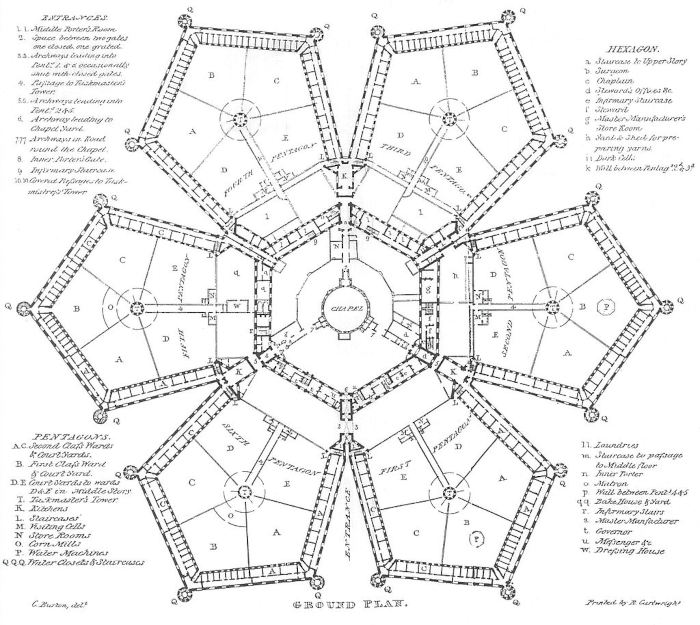

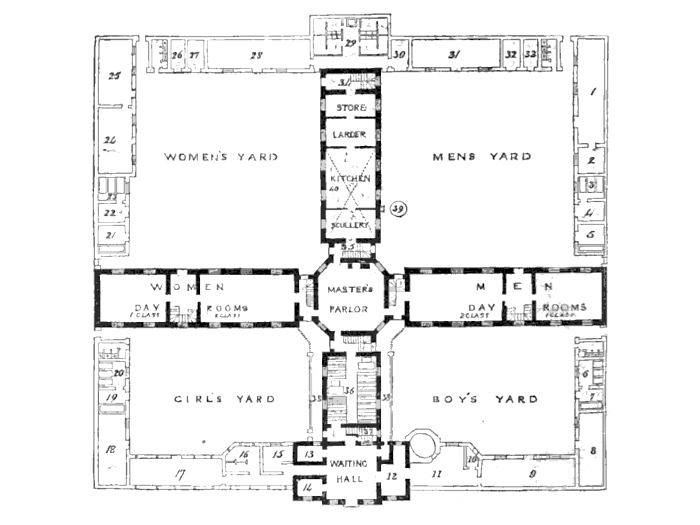

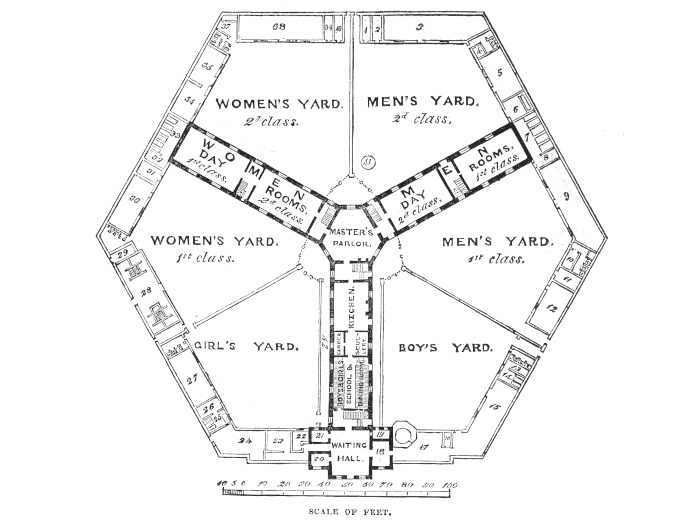

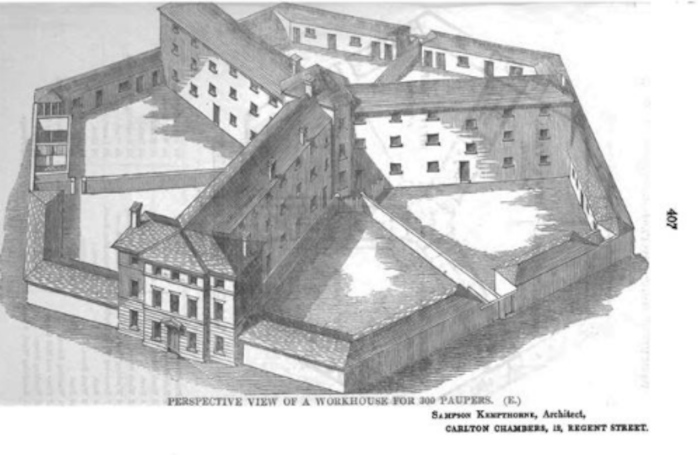

The hexagonal model was Sampson Kempthorne’s personal favourite. It was designed to contain three hundred paupers. The major difference and defining characteristic of this typology was the division of its hexagonal base obtained from the boundary-defining outer blocks by three ranges emanating from the central hub. This specific formulation of the architectural mass provided three internal yards that were further divided by self-standing walls in half to acquire six separated yards. Kempthorne put the hexagonal model ahead of others largely because of the advantageous solution of obtaining six courtyards that could separate all children, adult, and elderly paupers according to their gender.

Bentham advocated “Pauper Management” which involved the creation of a chain of large workhouses.

Between 1835 and 1838, twenty-six workhouses were built all around the nation based on the hexagonal model. Sixteen of these were designed by Sampson Kempthorne, and ten were attributed to his followers and competitors. The arrangement of the plan was quite similar to the cruciform model. Some particular differences included the transfer of the kitchen, the dining room, and the receiving wards to the front range; the piggery to the adult women’s yard; and the laundry to the elderly women’s yard.

In addition to the segregation of married couples, one of the most controversial regulations of the union workhouse was deemed the separation of parents from their children and children from their siblings. In the architectural layout of workhouses, boys and girls had their separate day rooms, dormitories, infirmaries, and their own airing yards, as was the case at Andover. Although mothers were officially permitted to have access to their children under seven years of age, these rules were usually manipulated by the guardians to put mothers to work” more efficiently.”.

This form of separation was a primary concern because indoor pauper children under sixteen constituted more than one third of the entire pauper population within union workhouses during the mid-nineteenth century. Institutional workhouse architecture was accused of depriving pauper children of “all communication with those who were near and dear to them,” and closing them up “like birds in a cage.” Along with the difficulties deriving from emotional isolation, children’s worst enemies were sheer boredom and repetitive monotony of everyday workhouse life.

Utilitarianism was revised and expanded by Bentham's student John Stuart Mill, who sharply criticized Bentham's view of human nature, which failed to recognize conscience as a human motive. Mill considered Bentham's view “to have done and to be doing very serious evil.” In Mill's hands, “Benthamism” became a major element in the liberal conception of state policy objectives.

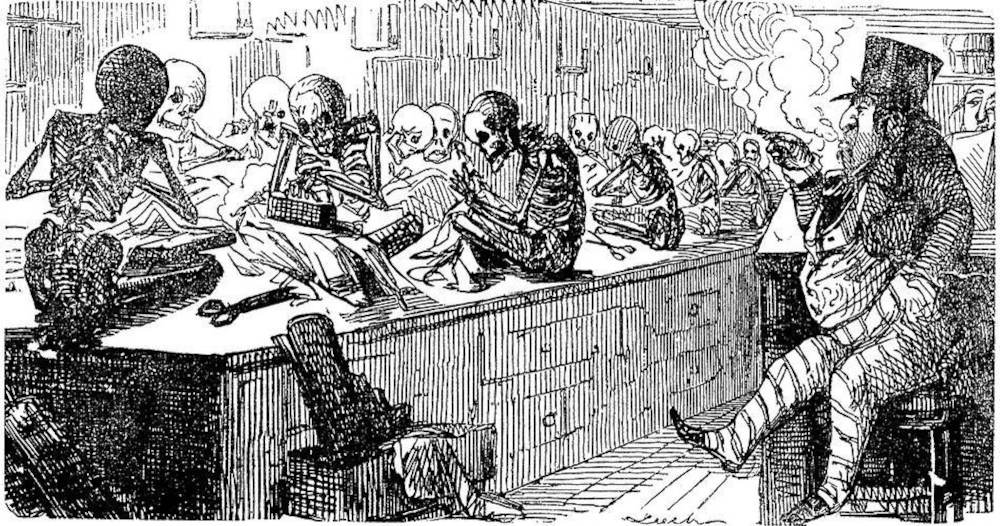

A typical Sunday for pauper children was "one lasting agony," as "they had dinner at twelve and tea at six, confined during the yawning interval in the dull day-room with nothing to do but to look at the clock, and then out of the window, and then back at the clock again." They were separated from their family and siblings, forced to wear the same dull gray uniforms as others, and ordered to be silent and still under strict institutional regulations.

The combination of isolation, lack of activities, and harsh workhouse discipline was observed to influence children’s everyday moods and behaviours in problematic ways. According to” The English Bastile” in Social Sciences Review, workhouse children “neither laugh as ordinary free children do, nor move like them; when they laugh they tremble, when they run, they shuffle, and when they come in obedience to a call, they cringe.

No moral concept suffers more at Bentham's hand than the concept of justice. There is no sustained, mature analysis of the notion.”.

Bentham's proposal would soon be adopted by Chadwick word by word in compiling the New Poor Law report in terms of not only the centralized and homogenous dissemination of workhouses on the national scale, but also the conceived architectural scheme focusing on the centralized supervision, utilitarian discipline, and moral control of the paupers within new workhouse buildings embodying panoptic principles.

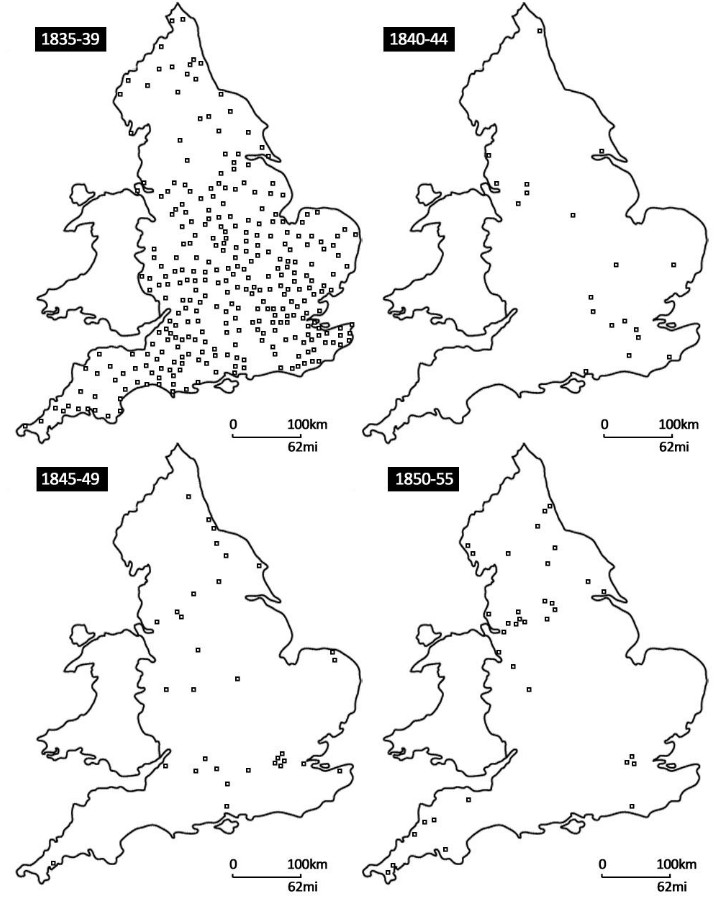

The analysis of the historical geography of union workhouse, still in the mid-nineteenth century, makes visible some dimensions of the building program that were hither too unavailable. The contrast between the industrial North and agricultural South, for starters, can be read directly from the level of local resistance of union boards who consciously refrained from constructing union workhouses and searched for alternatives. Also, the emergence period of the union workhouse system between 1834, the enactment of the New Poor Law, and 1847, the dissolution of the Poor Law Commission, is underlined by the proportionate building activity of this period.

Andover workhouse scandal

The scandal began with the revelation in August 1845 that inmates of the workhouse in Andover, Hampshire, England were driven by hunger to eat the marrow and gristle from (often putrid) bones, which they were to crush to make fertilizer. The inmates' rations set by the local Poor Law guardians were less than the subsistence diet decreed by the central Poor Law Commission (PLC), and the master of the workhouse was diverting some of the funds, or the rations, for private gain. The guardians were loath to lose the services of the master, despite this and despite allegations of the master's drunkenness on duty and sexual abuse of female inmates.

The workhouse master produced ten or twelve paupers, who confirmed the tale; they said that they fought each other for the bones if they were fresh, but they were so hungry that they ate the marrow even when the bones were putrid.

Three and a half “one gallon” bread loaves (each weighing 8 pounds and 11 ounces) per week were considered necessary for a man in 1795. By November 1830, the ration in the Andover area had been reduced to one quarter of a loaf per day (i.e., reduced by half). The Housemaster Colin McDougal was accused of 'frequently taken liberties with the younger women and girls in this house, and attempted at various times to prevail upon them, by force or otherwise, to consent to gratify his wishes; that he has actually had criminal intercourse with some of the female inmates, and for a length of time has been guilty of drunkenness and other immoralities'. The prosecution listed over a hundred witnesses, and it would have taken three months to hear them all if the Poor Law Commission had suspended the inquiry.

Children ate the food waste and raw potatoes they were supposed to feed the pigs, women were often sexually assaulted, and inmates who disobeyed orders were sometimes forced to sleep in the workhouse’s morgue as punishment. The workhouse master was so bad that 61 people from the workhouse committed major crimes between 1837 and 1845 just to be sent to jail and out of the workhouse.

Huddersfield workhouse scandal

The Huddersfield workhouse scandal concerned the conditions in the workhouse at Huddersfield, England in 1848. The problems included overcrowding, disease, food, and sanitation, among others. A report, for instance, described the workhouse as “wholly unfitted for residence for the many scores that are continually crowded into it, unless it be that desire to engender endemic and fatal disease. And this Huddersfield workhouse is by far the best in the whole union.”. On investigation, the conditions at Huddersfield were considered to be worse than those in Andover, which had hit the headlines in Britain two years earlier.

In 1857, a special commission found that lack of classification at Huddersfield resulted in 'abandoned women' with diseases of a 'most loathsome character' being mixed together with idiots, young children, and lying-in cases. There were even cases of the living languishing alongside the dead.

This previous scandal gained notoriety due to extreme abuses, with accounts citing workhouse inmates getting so hungry they had resorted to chewing on the bones that they were grinding down for fertilizer. These two incidents contributed to the growth of demands for social reform as reflected by later developments such as the intensified public discourse on the Poor Law The overseers of the poor of the township of Huddersfield, having received it in instruction from a vestry meeting of the township (assembled on the 23rd day of March last, to nominate fit and proper persons to fill the said office of overseers), to institute an inquiry into certain allegations then and there made, as to the general treatment of the sick poor had received in the Huddersfield workhouse, beg to say that they have complied with the request contained in the resolution of the said vestry meeting, and have thereupon to report as follows:-

Patients have been allowed to remain for nine weeks together without change of linen or of bed clothing: that beds in which patients suffering in typhus have died, one after another, have been again and again and repeatedly used for fresh patients, without any change or attempt at purification; that the said beds were only bags of straw and shavings, for the most part, laid on the floor, and that the whole swarmed with lice; that two patients suffering in infectious fever, were almost constantly put together in one bed; that it did not infrequently happen that one would be ragingly delirious, when the other way dying; and that it is a fact that a living patient has occupied the same bed with a corpse for a considerable period after death; that the patients have been for months together without properly appointed nurses to attend to them; that there has been for a considerable time none but male paupers to attend on female patients; that when the poor sick creatures were laid in the most abject and helpless state — so debilitated as to pass their dejections as they lay, they have been suffered to remain in the most befouled state possible, besmeared in their own excrement, for days together and not even washed.

Of the general treatment of the poor in the workhouse, the Overseers have to report that the house is, and has been for a considerable period, crowded out with inmates; that there are forty children occupying one room eight yards by five; that these children sleep four, five, six, seven, and even ten, in one bed; that thirty females live in another room of similar size; and that fifty adult males have to cram into a room seven and a half yards long by six yards wide. The clothing of the establishment is miserably deficient; that there is no clothing in stock; that a great proportion of the inmates are obliged to wear their own clothes; that others have little better than rags to cover them.

The Huddersfield Board of Guardians took over all the existing township workhouses and decided to retain the fave largest at Huddersfield, Almondbury, Kirkheaton, Golcar, and Honley, and to close other smaller workhouses. At the Golcar Workhouse, Poor Law Board Inspector RB Cane found the workhouse “wholly inadequate in every respect”. The men slept two to a same bed, with up to 14 in one small room containing seven beds. At the time of his visit, seven women and five children occupied four beds in one small room, which also served as the lying-in ward. The kitchen and washhouse were a small lean-to shed, and the inmates “puddings” were boiled in the same copper as the foul linen was boiled and washed.

Husbands, wives and children were kept separate and forbidden to speak to each other except at certain times.

Kirkheaton workhouse was described in an October 1866 inspection as “an old, dilapidated building with none of the requisites of a workhouse. Ventilation, in the proper sense, does not exist. It could accommodate 50 inmates, and at this date it residents comprised of 2 men, 6 women, 16 boys, 21 girls, and 2 infants. The women, girls and infants, 29 in number, occupied 13 beds in another part of the house. Two of the elder girls, affected by “incontinence of urine”, slept together in the same bed. Three of the boys in the habit of “wetting the beds” slept together in the same bed, which was in an abominable condition — the urine had not only saturated the bedding and the boards beneatch the bed, but had found its way through the floor into the room below. The copper in which the foul linen is-boiled is used also for cooking the food of the inmates.

Benthams cruel theory ultimately decreed that it would be acceptable to torture one person if this would produce an amount of happiness in other people outweighing the unhappiness of the tortured individual.

In October 1866 RB cane visited what he referred to as the Honley workhouse. He expressed regret that “…so ill-arranged and incomplete a building was ever erected, with many parts of the building having been converted to uses for which they were never intended. For example, the vagrant wards had been converted into men's sick wards, the female receiving ward had been made into a bathroom for female idiots, and the male receiving ward was used as an infirm ward. The children, 24 in number, had no day rooms. The boys associate with the adult male paupers and the girls with the able-bodied women, with no separation at night. All the water closets were constructed such that the foul air was drawn inwards and into the main body of the house. Despite the report, it took much longer to clean up the workhouse than expected. By 1870, Huddersfield was still well behind other workhouses in providing better care for their residents.

In Laurie Lee’s ‘Cider With Rosie’, an account of life in a Gloucestershire village in the 1920s. The author tells the story of Joseph and Hannah Brown, who had lived in the same house for fifty years, ‘never out of each other’s company’. One day, the ‘Authorities’ decided they were too frail to look after each other any longer, and they should be moved to the Workhouse. Lee describes the couple’s shock and terror as they lay, clutching each other’s hands. Hannah and Joseph thanked the Visiting Spinsters but pleaded to be left at home, to be left as they wanted, to cause no trouble, just simply to stay together.

Always a word of shame, grey shadow falling on the close of life, most feared by the old; …abhorred more than debt, or prison, or beggary, or even the stain of madness.

‘You’ll be well looked after,’ the Spinsters said, ‘and you’ll see each other twice a week.’ The bright, busy voices cajoled with authority and the old couple were not trained to defy them. So that same afternoon, white and speechless, they were taken away to the Workhouse. Hannah Brown was put to bed in the Women’s wing, and Joseph lay in the Men’s. It was the first time, in all their fifty years, that they had ever been separated. They did not see each other again, for in a week they both were dead.

The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.