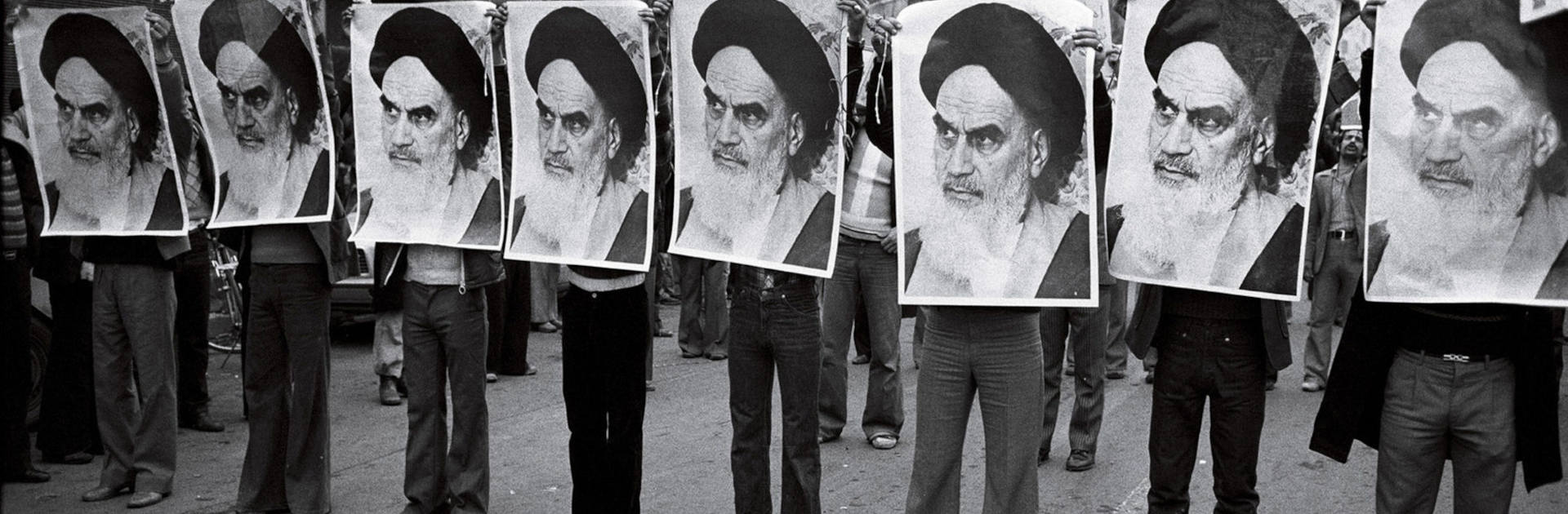

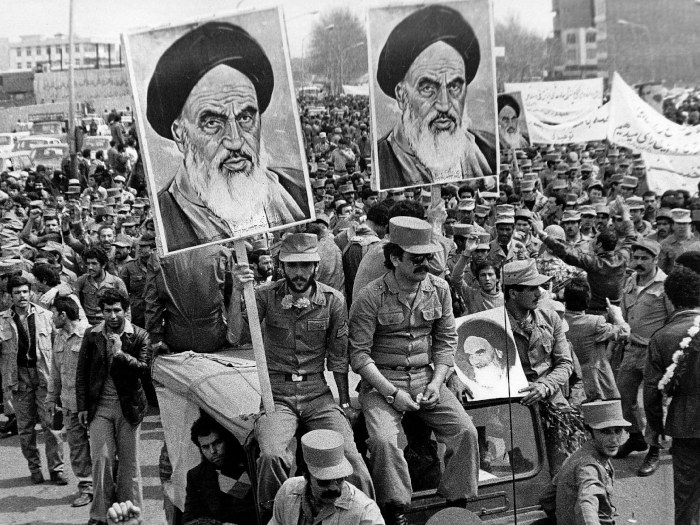

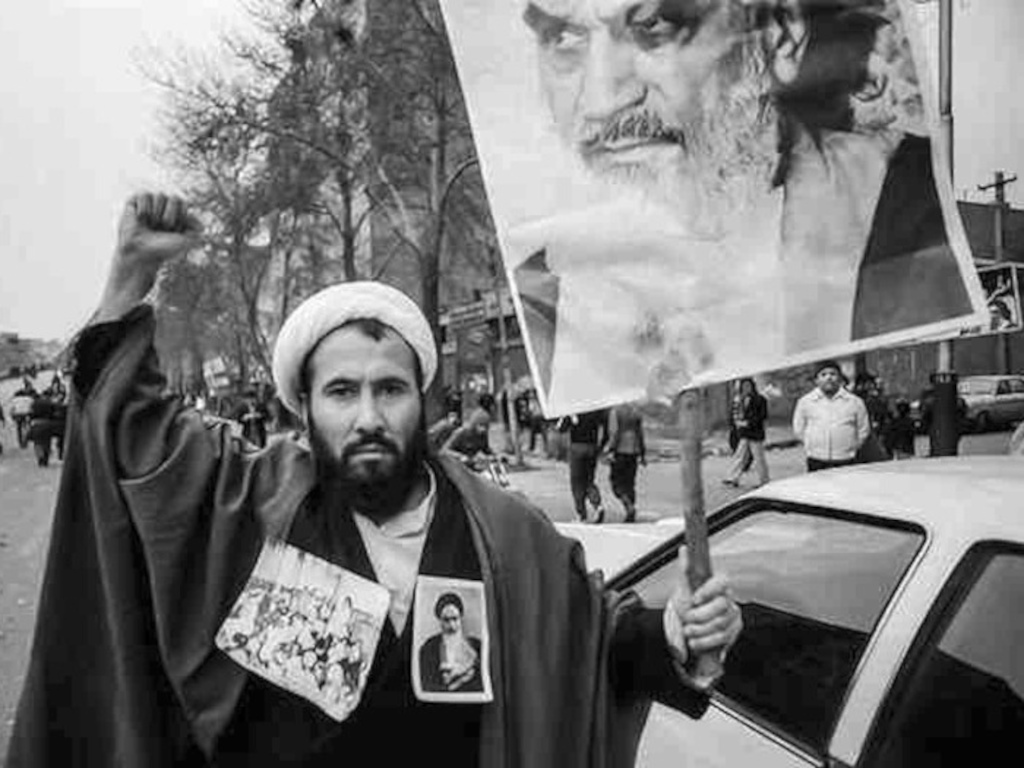

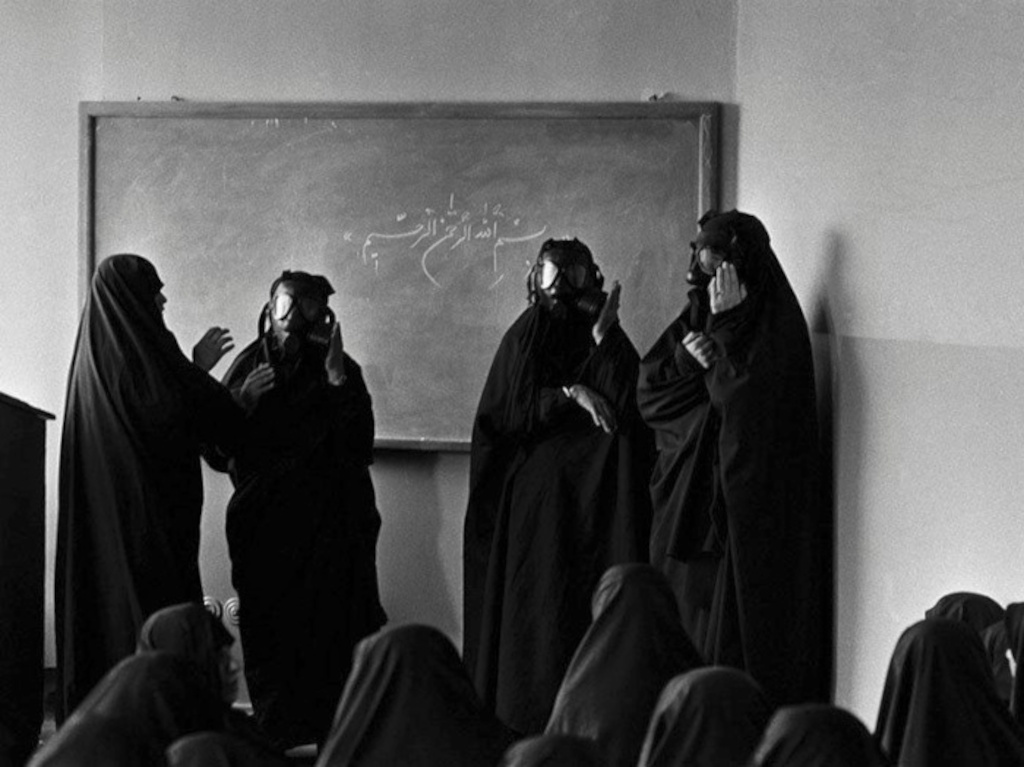

Communist insurgents parade personality cult portraits of their despotic dictator Ruhollah Khomeini.

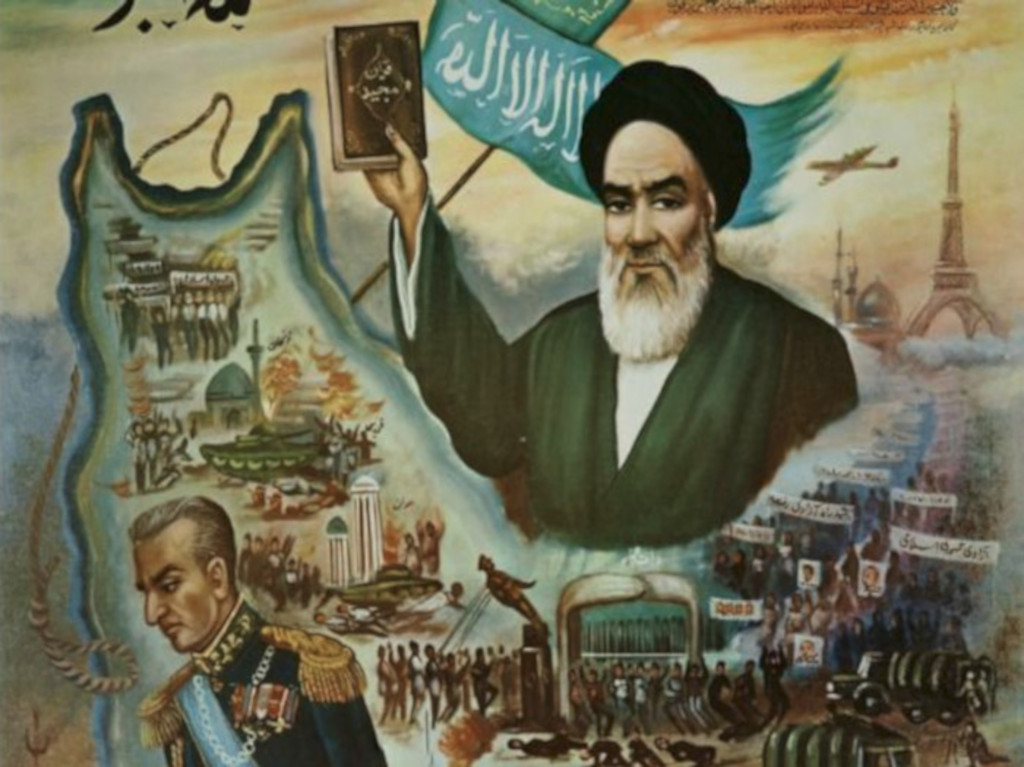

Iran

Iran suffered a Maoist revolution replacing the Little Red Book with contorted interpretations of the Koran. The template of this revolution is being wagered upon western Christianity through subordinance to socialism. Marxism should be pulled out from every religion to halt sweeping encroachment of socialised universalism.

Forward

Before the 1979 revolution the Persian Empire had a 2500 year old dynasty. The Achaemenid Empire, also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire that was based in Western Asia and founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC.

The Shah held a national event in Iran that consisted of an elaborate set of grand festivities and took place from 12–16 October 1971 to celebrate the founding of the ancient Achaemenid Persian Empire.

The intent of the celebration was to highlight Iran's ancient civilisation and history as well as to showcase its contemporary advances under Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran. The celebrations highlighted Iran's Aryan roots and pre-Islamic origins while promoting Cyrus the Great as a national hero.

Some later historians argue that this massive celebration contributed to events that culminated in the 1979 Iranian Revolution, although others argue that the extravagance of the proceedings were exaggerated by revolutionaries motivated to discredit the Shah's regime. However, the Shah only approved the celebration plans after the scope was reduced to one-quarter of the original plan in order to reduce costs.

Imperial State of Iran

The Imperial State of Iran was the official name of Iran under rule of the Pahlavi dynasty. The polity was formed in 1925 and lasted until 1979, when the monarchy was overthrown and abolished as a result of the Iranian Revolution. The dynasty was founded by Reza Shah Pahlavi in 1925, a former brigadier-general of the Persian Cossack Brigade, whose reign lasted until 1941, when he was forced to abdicate by the Allies after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. He was succeeded by his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran.

Following the coup d'état in 1953 supported by the United Kingdom and the United States, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's rule became more autocratic and became firmly aligned with the Western Bloc during the Cold War. In correspondence with this reorientation of Iran's foreign policy, Iran became a client state of the United States in order to act as a bulwork against Soviet expansion and this gave the Shah the political capital to enact a hitherto unprecedented socio-economic program that would transform all aspects of Iranian life through the White Revolution.

Although Iran, also called Persia, was the world's oldest empire, dating back 2,500 years, by 1900 it was floundering. Bandits dominated the land; literacy was one percent; and women, under archaic Islamic dictates, had no rights. The Shah changed all this. Primarily by using oil-generated wealth, he modernised the nation. He built rural roads, postal services, libraries, and electrical installations. He constructed dams to irrigate Iran's arid land, making the country 90-percent self-sufficient in food production. He established colleges and universities, and at his own expense, set up an educational foundation to train students for Iran's future.

Before the Islamic Revolution there was no restriction on dress and living, nor religious restrictions. At that time Iran was considered to be the most modern among Islamic countries and Iran’s environment was no less than that of cities like Paris or London.

Consequently, Iran experienced prodigious success in all indicators ranging from literacy, to health, to standard of living. However, by 1978 the Shah faced growing public discontent which culminated into a full-fledged popular revolutionary movement led by the radical Shia cleric Ruhollah Khomeini. The second Pahlavi went into exile with his family in January 1979, sparking a series of events that quickly led to the end of both of the monarchy and the state and the beginning of the Islamic Republic of Iran on 11 February 1979. Following Pahlavi's death in 1980, his son, Reza Pahlavi, now leads the family throne in exile.

Ruhollah Khomeini

Ruhollah Khomeini ancestors migrated towards the end of the 18th century from their original home in Nishapur, Khorasan Province, in northeastern part of Iran, for a short stay, to the Kingdom of Awadh, a region in the modern state of Uttar Pradesh, India, whose rulers were Twelver Shia Muslims of Persian origin. The family eventually settled in the small town of Kintoor, near Lucknow, the capital of Awadh. Ayatollah Khomeini's paternal grandfather, Seyyed Ahmad Musavi Hindi, was born in Kintoor.

Khomeini studied Greek philosophy and was influenced by both the philosophy of Aristotle, whom he regarded as the founder of logic, and Plato, whose views "in the field of divinity" he regarded as "grave and solid". Among Islamic philosophers, Khomeini was mainly influenced by Avicenna and Mulla Sadra, it has been said that one of Khomeini's biggest influences was a teacher named Mirza Muhammad, 'Ali Shahabadi, and a variety of historic Sufi mystics, including Mulla Sadra and Ibn Arabi.

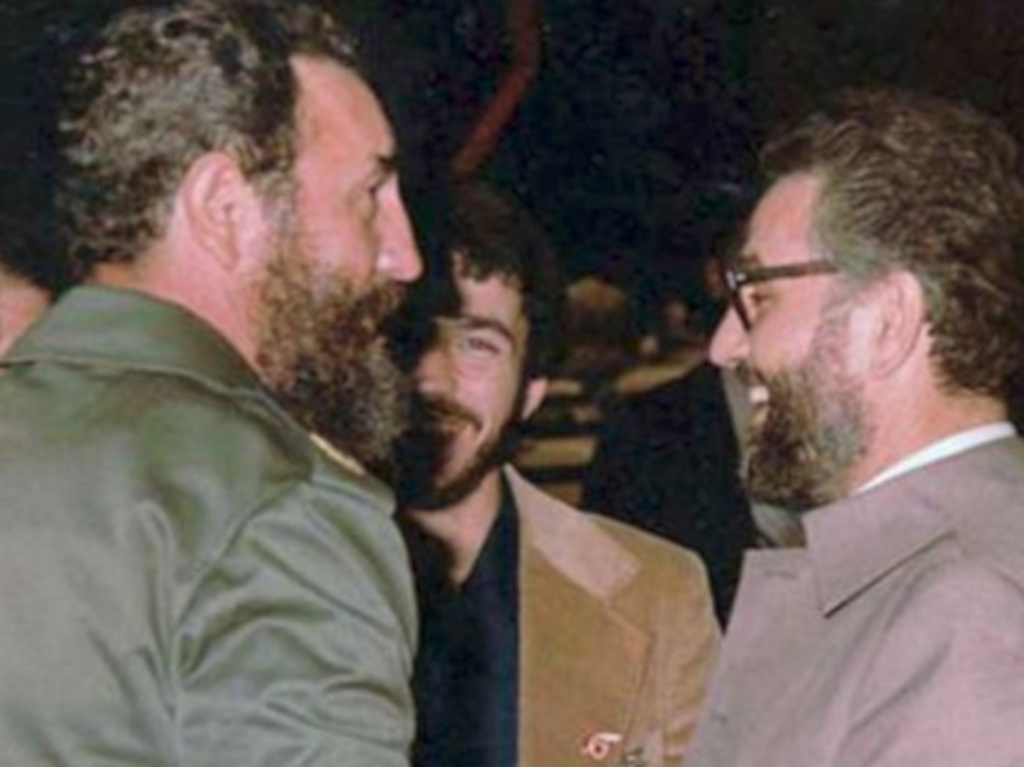

Khomeini spent more than 14 years in exile, mostly in the Iraq city of Najaf. Initially, he was sent to Turkey on 4 November 1964 where he stayed in Bursa in the home of Colonel Ali Cetiner of the Turkish Military Intelligence. In October 1965, after less than a year, he was allowed to move to Najaf, Iraq, where he stayed until 1978, when he was expelled by then-Vice President Saddam Hussein.

Above: View of the entrance gate to Rue de Chevreuse, close to the cottage which served as Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini's operational and media headquarters during his four month stay in October 1978, in Neauphle-Le-Chateau, west of Paris. Sheltered in a cottage in a sleepy village outside Paris, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini piped out messages daily to hundreds of followers clamoring to glimpse their glowering idol with black turban, and amplified his pronouncements with recorded messages to Iranians at home, turning his humble abode into an international megaphone for the Islamic revolution.

Khomeini arrived at Paris' Orly airport on Oct. 6, 1978. Entering with a tourist visa he spent a few days in the southern suburb of Cachan, where Bani-Sadr then lived, before relocating to Neauphle-le-Chateau, 25 miles west of Paris. While in Paris, Khomeini had "promised a democratic political system" for Iran, but once in power, he advocated for the creation of theocracy based on the Velayat-e faqih. Khomeini's inner circle included Abolhassan Banisadr, Sadegh Ghotbzadeh (executed in 1982), Ibramhim Yazdi and three mullahs.

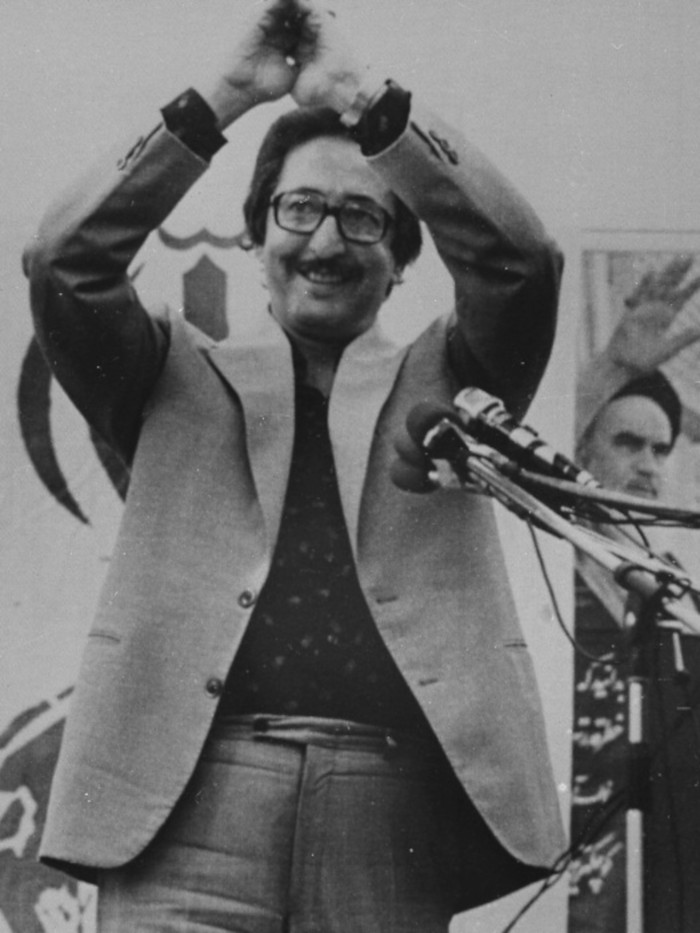

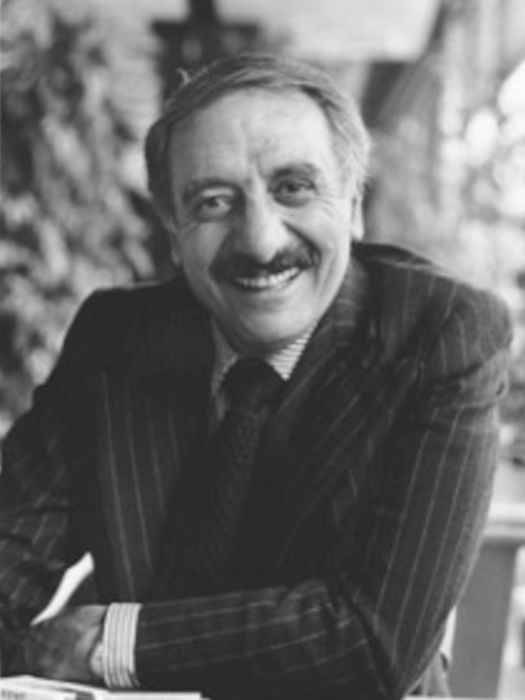

Abolhassan Banisadr

Banisadr resided for many years in France where he co-founded the National Council of Resistance of Iran. He was elected as president on 25 January 1980 but was impeached on 21 June 1981. Banisadr fled Iran disguised as a woman arriving in Paris with shaved eyebrows and dressed in a skirt.

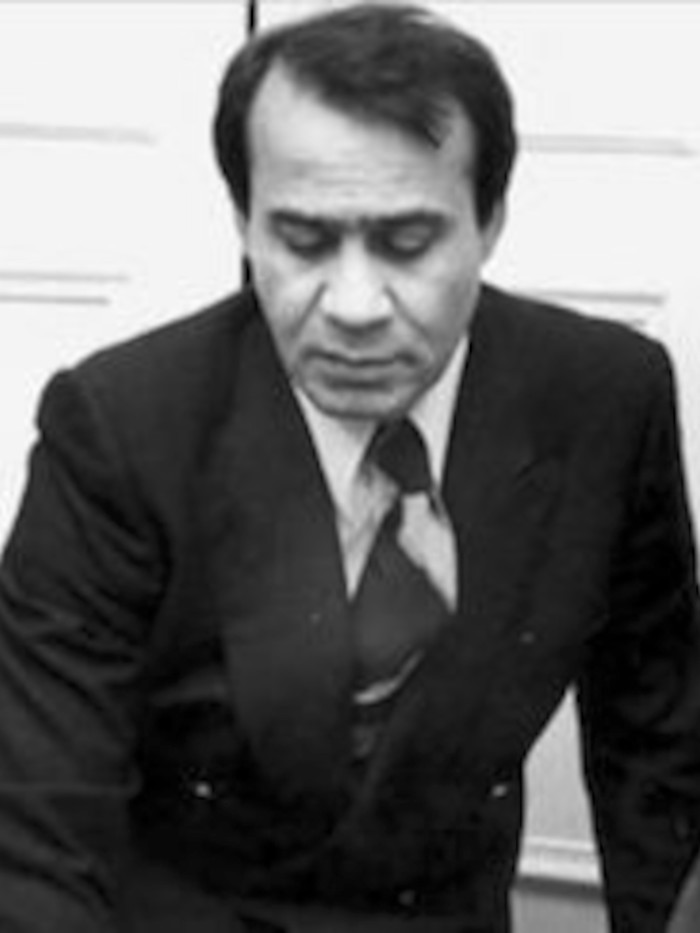

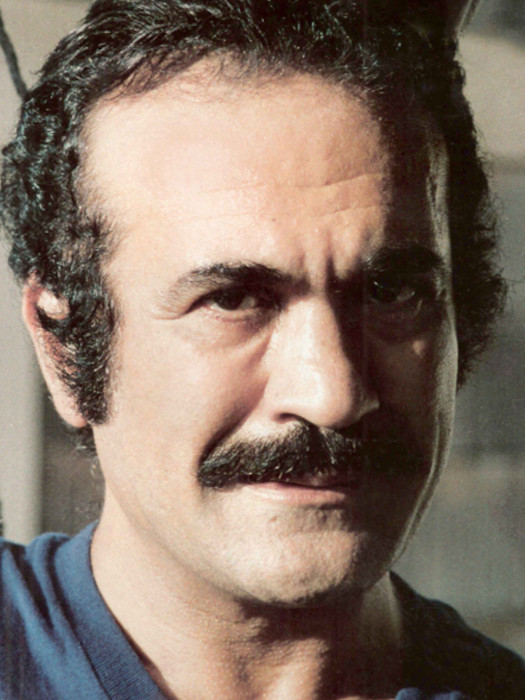

Sadegh Ghotbzadeh

Served as a close aide of Ayatollah Khomeini during his 1978 exile in France, and foreign minister during the Iran hostage crisis following the Iranian Revolution. In 1982, he was executed for allegedly plotting the assassination of Ayatollah Khomeini and the overthrow of the Islamic Republic.

Ebrahim Yazdi

From 1995 until 2017 (his resignation was never accepted), Yazdi headed the Freedom Movement of Iran. He served as deputy prime minister and minister of foreign affairs in the interim government of Mehdi Bazargan, until his resignation in November 1979, Yazdi fled Iran and died exiled in Turkey.

Beginning in 1981, Banisadr lived in Versailles, near Paris, in a villa closely guarded by French police. Political asylum in Paris was conditional on abstaining from anti-Khomeini activities in France.

Each was in charge of a task, including dealing with the media whose coverage boosted Khomeini's profile. Banisadr said he and a group of friends fashioned or vetted the messages Khomeini delivered — based on what they were told Iranians wanted to hear. Tape recordings of his statements were sold in Europe and delivered to Iran. Other messages went out by telephone, read to supporters in various Iranian towns, where they were disseminated.

the Jewish agent, the American serpent whose head must be smashed with a stone

Cassette copies of Khomeini's lectures fiercely denouncing the Shah eventually became common items in the markets of Iran, helping to demythologise the power and dignity of the Shah and his reign. The plaque in the garden of Neauphle-le-Chateau, inscribed in French and Farsi, says the village name "is forever registered in the history of French-Iranian relations."

But the Iran's Islamist government quickly toughened, and France soon was vilified as "the little Satan" when it began taking in members of the Iranian opposition, said Nicoullaud, the former ambassador. Aware of the importance of broadening his base, Khomeini reached out to Islamic reformist and secular enemies of the Shah, despite his long-term ideological incompatibility with them.

On Thursday, 1 February 1979, Khomeini returned to Iran, welcomed by a crowd estimated (by the BBC) to be of up to five million people. On his chartered Air France flight back to Tehran, he was accompanied by 120 journalists; one of the journalists, Peter Jennings, asked: "Ayatollah, would you be so kind as to tell us how you feel about being back in Iran?" Khomeini answered via his aide Sadegh Ghotbzadeh: "Hichi" meaning nothing. [Year Zero agenda]

We always said it was the journalists who paid the return voyage of the ayatollah.

Khomeini adamantly opposed the provisional government of Shapour Bakhtiar, promising "I shall kick their teeth in. I appoint the government.". On 11 February (Bahman 22), Khomeini appointed his own competing interim prime minister, Mehdi Bazargan, demanding, "since I have appointed him, he must be obeyed." It was "God's government," he warned, disobedience against him or Bazargan was considered a "revolt against God.". This led to the purge or replacement of many secular politicians in Iran.

The day after the victory of the revolution, on 2 February 2 1979, several foreign embassies in Tehran, including those of the United States, the United Kingdom, and Yugoslavia were over-run by groups identifying themselves as leftist revolutionaries.

Khomeini preached the danger of plots by foreigners and their Iranian agents throughout his political career. His belief, common among all political persuasions in Iran, can be explained by the domination of Iran's politics for the past 200 years until the Islamic revolution, first by Russia and Britain, later the United States. Foreign agents were involved in all of Iran's three military coups: 1908 [Russian], 1921 [British] and 1953 [UK and US].

He also held the West responsible for a host of contemporary problems. He charged that colonial conspiracies kept the country poor and backward, exploited its resources, inflamed class antagonism, divided the clergy and alienated them from the masses, caused mischief among the tribes, infiltrated the universities, cultivated consumer instincts, and encouraged moral corruption, especially gambling, prostitution, drug addiction, and alcohol consumption.

The Ayatollah's health declined several years prior to his death. After spending eleven days in Jamaran hospital, Ruhollah Khomeini died on 3 June 1989 after suffering five heart attacks in just ten days, at the age of 89 just before midnight. arge numbers of Iranians took to the streets to publicly mourn his death and in the scorching summer heat, fire trucks sprayed water on the crowds to cool them.

Official Iranian estimates gave the size of the crowds, lining the 32-km 20-mile route to Tehrans Behesht-e Zahra cemetery on June 11, 1989, for the funeral of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini as 10,200,000 people, that is one-sixth of the population of Iran. Western agencies etimated that 2 million paid their respects as the body lay in state. At least 10 mourners were trampled to death, more than 500 were badly hurt and several thousand more were treated for injuries sustained in the ensuing pandemonium.

Military

Iranian Armed Forces are the largest in the Middle East in terms of active troops. Iran's military forces are made up of approximately 610,000 active-duty personnel plus 350,000 reserve and trained personnel that can be mobilised when needed, bringing the country's military manpower to about 960,000 total personnel. These numbers do not include Law Enforcement Force or Basij.

Most of Iran's imported weapons consist of American systems purchased before the 1979 Islamic Revolution, with limited purchases from the Soviet Union in the 1990s following the Iran–Iraq War. However, the country has since then launched a robust domestic rearmament program, and its inventory has become increasingly indigenous.

Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps is a branch of the Iranian Armed Forces, founded after the Iranian Revolution on 22 April 1979 by order of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Whereas the Iranian Army defends Iranian borders and maintains internal order, according to the Iranian constitution, the Revolutionary Guard is intended to protect the country's Islamic republic political system.

The Revolutionary Guards base their role in protecting the Islamic system as well as preventing foreign interference and coups by the military or "deviant movements". As of 2011, the Revolutionary Guards had at least 250,000 military personnel including ground, aerospace and naval forces. Its naval forces are now the primary forces tasked with operational control of the Persian Gulf. It also controls the paramilitary Basij militia which has about 90,000 active personnel. Its media arm is Sepah News.

From its origin as an ideologically driven militia, the IRGC has taken an ever more assertive role in virtually every aspect of Iranian society. Its part in suppressing dissent has led many analysts to describe the events surrounding the 12 June 2009 presidential election as a military coup, and the IRGC as an authoritarian military security government for which its Shiite clerical system is no more than a facade.

In December 2009 evidence uncovered during an investigation by the Guardian newspaper and Guardian Films linked the IRGC to the kidnappings of 5 Britons from a government ministry building in Baghdad in 2007. Three of the hostages, Jason Creswell, Jason Swindlehurst and Alec Maclachlan, were killed. Alan Mcmenemy's body was never found but Peter Moore was released on 30 December 2009. The investigation uncovered evidence that Moore, 37, a computer expert from Lincoln was targeted because he was installing a system for the Iraqi Government that would show how a vast amount of international aid was diverted to Iran's militia groups in Iraq.

According to Geneive Abdo IRGC members were appointed "as ambassadors, mayors, cabinet ministers, and high-ranking officials at state-run economic institutions" during the administration of president Ahmadinejad. Appointments in 2009 by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei have given "hard-liners" in the guard "unprecedented power" and included "some of the most feared and brutal men in Iran.".

In May 2019, the United States accused the IRGC of being "directly responsible" for an attack on commercial ships in the Gulf of Oman. Michael M. Gilday, United States director of the Joint Staff, described US intelligence attributing that the IRGC used limpet mines to attack four oil tankers anchored in the Gulf of Oman for bunkering through the Port of Fujairah. Since 15 April 2019, the United States, which opposes the activities of Sepah, considers the IRGC as a terrorist organisation, which some top CIA and Pentagon officials reportedly opposed.

On 8 April, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu tweeted in Hebrew that America's terrorist designation was the fulfillment of "another important request of mine." This designation was criticised by a number of governments including Turkey, Iraq and China as well as the Islamic Consultative Assembly, Iran's parliament, in which members wore IRGC uniforms in protest.

Since the designation, the United States Department of State’s Rewards for Justice Program has offered a reward of up to USD $15 million for financial background information about the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and its branches, including an IRGC financier, Abdul Reza Shahlai, who it says was responsible for a raid that killed five American soldiers in Karbala, Iraq on 20 January 2007.

Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War was a protracted armed conflict that began on 22 September 1980 with a full-scale invasion of Iran by neighbouring Iraq. The war lasted for almost eight years, and ended in a stalemate on 20 August 1988, when Iran accepted Resolution 598 of the United Nations Security Council. Iraq's primary rationale for the invasion was to cripple Iran and prevent Ruhollah Khomeini from exporting the 1979 Iranian Revolution movement to Shia-majority Iraq and internally exploit religious tensions that would threaten the Sunni-dominated Ba'athist leadership led by Saddam Hussein.

In total, around 500,000 people were killed during the war (with Iran bearing the larger share of the casualties), excluding the tens of thousands of civilians killed in the concurrent Anfal campaign targeting Kurds in Iraq. The end of the war resulted in neither reparations nor border changes.

The conflict has been compared to World War I in terms of the tactics used, including large-scale trench warfare with barbed wire stretched across fortified defensive lines, manned machine gun posts, bayonet charges, Iranian human wave attacks, extensive use of chemical weapons by Iraq, and deliberate attacks on civilian targets. A notable feature of the war was the state-sanctioned glorification of martyrdom to Iranian children, which had been developed in the years before the revolution. The discourses on martyrdom formulated in the Iranian Shia Islamic context led to the tactics of "human wave attacks" and thus had a lasting impact on the dynamics of the war.

Human Rights

Under the Islamic Republic, the prison system was centralised and drastically expanded, in one early period (1981-1985) more than 7900 people were executed. According to Abrahamian, in the eyes of Iranian officials, "the survival of the Islamic Republic – and therefore of Islam itself – justified the means used," and trumped any right of the individual. The vast majority of killings of political prisoners occurred in the first decade of the Islamic Republic, after which violent repression lessened.

Between January 1980 and June 1981 another 900 executions (at least) took place, for everything from drug and sexual offenses to "corruption on earth", from plotting counter-revolution and spying for Israel to membership in opposition groups. And in the year after that, at least 8,000 were executed.

The 1988 executions of Iranian political prisoners was a series of state-sponsored execution of political prisoners across Iran, starting on 19 July 1988 and lasting for approximately five months. The majority of those killed were supporters of the People's Mujahedin of Iran, although supporters of other leftist factions, including the Fedaian and the Tudeh Party of Iran (Communist Party), were executed as well. The killings have been described as a political purge without precedent in modern Iranian history, both in terms of scope and coverup.

Amnesty International, after interviewing dozens of relatives, puts the number in thousands; and then-Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini's deputy, Hussein-Ali Montazeri put the number between 2,800 and 3,800 in his memoirs, but an alternative estimation suggests that the number exceeded 30,000. Because of the large number, prisoners were loaded into forklift trucks in groups of six and hanged from cranes in half-hour intervals.

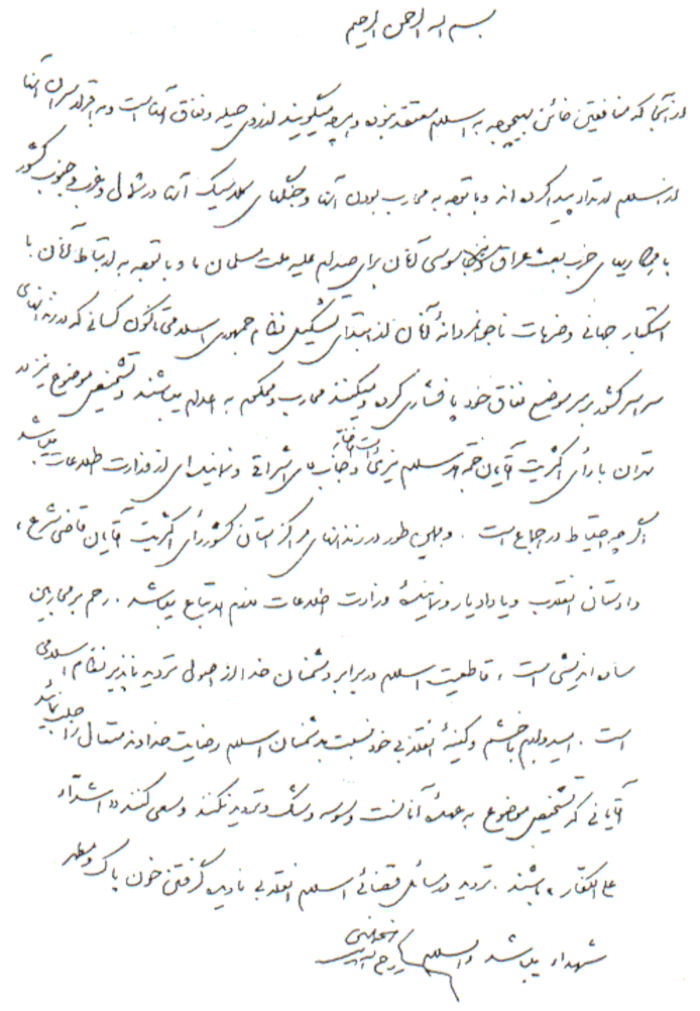

Shortly before the executions commenced, Iranian leader Ruhollah Khomeini issued "a secret but extraordinary order – some suspect a formal fatwa." This set up "Special Commissions with instructions to execute members of People's Mojahedin Organisation of Iran as moharebs (those who war against Allah) and leftists as mortads (apostates from Islam).".

In part the letter reads:

[In the Name of God, The Compassionate, the Merciful,]

As the treacherous Monafeqin [Mojahedin] do not believe in Islam and what they say is out of deception and hypocrisy, and

As their leaders have confessed that they have become renegades, and

As they are waging war on God, and

As they are engaging in classical warfare in the western, the northern and the southern fronts, and

As they are collaborating with the Baathist Party of Iraq and spying for Saddam against our Muslim nation, and

As they are tied to the World Arrogance, and in light of their cowardly blows to the Islamic Republic since its inception,

It is decreed that those who are in prison throughout the country and remain steadfast in their support for the Monafeqin [Mojahedin] are waging war on God and are condemned to execution.

Ayatollah Montazeri wrote to Ayatollah Khomeini saying "at least order to spare women who have children ... the execution of several thousand prisoners in a few days will not reflect positively and will not be mistake-free ... A large number of prisoners have been killed under torture by interrogators ... in some prisons of the Islamic Republic young girls are being raped ... As a result of unruly torture, many prisoners have become deaf or paralysed or afflicted with chronic diseases."

The first prisoners to be interviewed or "tried" were the male members of the People's Mujahedin of Iran, including those who had repented of their association with the group. The commission prefaced the proceedings with the false assurance that this was not a trial but a process for initiating a general amnesty and separating the Muslims from the non-Muslims. It first asked their organisational affiliation; if they replied "Mojahedin", the questioning ended there. If they replied monafeqin (hypocrites), the commission continued with such questions as:

- "Are you willing to denounce former colleagues?"

- "Are you willing to denounce them in front of the cameras?"

- "Are you willing to help us hunt them down?"

- "Will you name secret sympathisers?"

- "Will you identify phony repenters?"

- "Will you go to the war front and walk through enemy minefields?"

Almost all the prisoners answered "no" to at least one of the questions. These were then taken to another room and ordered to write their last will and testament and to discard any personal belongings such as rings, watches, and spectacles. They were then blindfolded and taken to the gallows where they were hanged in batches of six. Since "hanging" did not mean death by breaking of the neck by drop through a trap door, but stringing up the victim by the neck to suffocate, some took fifteen minutes to die.

After 27 August, the commission turned its attention to the leftist prisoners, such as members of the Tudeh, Majority Fedayi, Minority Fedayi, other Fedayi, Kumaleh, Rah-e Kargar, Peykar. These were also assured they were in no danger and asked:

- "Are you a Muslim?"

- "Do you believe in Allah?"

- "Is the Holy Qur'an the Word of Allah?"

- "Do you believe in Heaven and Hell?"

- "Do you accept the Holy Muhammad to be the Seal of the Prophets?"

- "Will you publicly recant historical materialism?"

- "Will you denounce your former beliefs before the cameras?"

- "Do you fast during Ramadan?"

- "Do you pray and read the Holy Qur'an?"

- "Would you rather share a cell with a Muslim or a non-Muslim?"

- "Will you sign an affidavit that you believe in Allah, the Prophet, the Holy Qur'an, and the Resurrection?"

- "When you were growing up, did your father pray, fast, and read the Holy Qur'an?"

Prisoners were told that authorities were asking them these questions because they planned to separate practicing Muslims from non-practicing ones. However, the real reason was to determine whether the prisoners qualified as apostates from Islam, in which case they would join the moharebs in the gallows. All this was a surprise to the prisoners, with one commenting: "In previous years, they wanted us to confess to spying. In 1988, they wanted us to convert to Islam.".

Mojahedin women were given equal treatment with Mojahedin men, almost all hanged as 'armed enemies of Allah'. However, for apostasy the punishment for women was different and lighter than that for men. Since according to the commission's interpretation of Islamic law, women were not fully responsible for their actions, "disobedient women – including apostates – could be given discretionary punishments to mend their ways and obey male superiors."

Leftist women—even those raised as practicing Muslims—were given another 'opportunity' to recant their 'apostasy.' "After the investigation, leftist women began to receive five lashes every day -- one for each of the five daily prayers missed that day, half the punishment meted out to the men. After a while, many agreed to pray, but some went on hunger strike, refusing even water. One died after 22 days and 550 lashes, and the authorities certified her death as suicide because it was 'she who had made the decision not to pray.'"

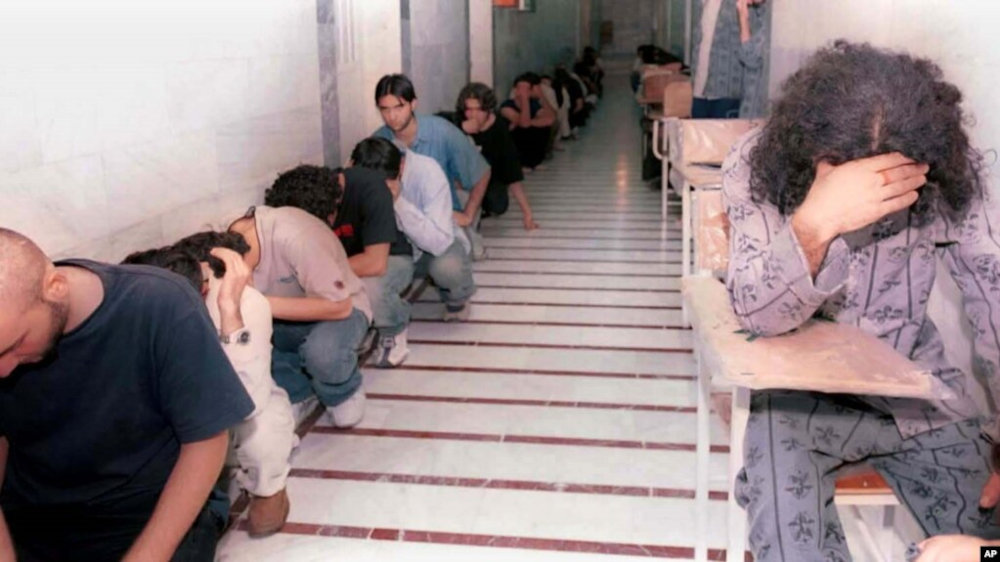

Iran’s police, intelligence and security forces, and prison officials subjected detainees to prolonged solitary confinement, beatings, floggings, stress positions, forced administration of chemical substances and electric shocks. Prison and prosecution authorities also deliberately denied prisoners of conscience and other prisoners held for politically motivated reasons adequate health care.

Conditions in many prisons and detention facilities remained cruel and inhuman. Prisoners suffered from overcrowding, limited hot water, unsanitary conditions, inadequate food and drinking water, insufficient beds and bathrooms, poor ventilation and insect infestations. The Penal Code continued to provide for corporal judicial punishments amounting to torture, including flogging, blinding, amputation, crucifixion and stoning.

In Iran, white torture has been practiced on political prisoners. Most political prisoners who experience this type of torture are journalists held in the Evin prison. "Amir Fakhravar, the Iranian white room prisoner, was tortured [at Evin prison] for 8 months in 2004. He still has horrors about his times in the white room.". It can include prolonged periods of solitary confinement, the use of continual illumination to deprive sleep often in detention centers outside the control of the prison authorities, including Section 209 of Evin Prison.

Ahmed Shaheed, the UN special human rights reporter in Iran, mentioned in a statement that human rights activist Vahid Asghari was psychologically tortured by means of long-term detention in solitary confinement and with threats to arrest, torture or rape his family members. He was also reportedly tortured with severe beatings for the purpose of eliciting confessions.

An Amnesty International report in 2004 documented evidence of "white torture" on Amir Fakhravar, by the Revolutionary Guards. According to the report, which called his case the first known example of white torture in Iran claimed that "his cells had no windows, and the walls and his clothes were white. His meals consisted of white rice on white plates. To use the toilet, he had to put a white piece of paper under the door. He was forbidden to speak, and the guards reportedly wore shoes that muffled sound".

In a telephone call to the Human Rights Watch in 2004, the Iranian journalist Ebrahim Nabavi made the following claim regarding white torture:

Since I left Evin, I have not been able to sleep without sleeping pills. It is terrible. The loneliness never leaves you, long after you are 'free.' Every door that is closed on you.... This is why we call it 'white torture.' They get what they want without having to hit you. They know enough about you to control the information that you get: they can make you believe that the president has resigned, that they have your wife, that someone you trust has told them lies about you. You begin to break. And once you break, they have control. And then you begin to confess.

Kianush Sanjari, an Iranian blogger and activist who had allegedly experienced this type of torture in 2006 claimed:

I feel that solitary confinement—which wages war on the soul and mind of a person—can be the most inhuman form of white torture for people like me, who are arrested solely for (defending) citizens' rights. I only hope the day comes when no one is put in solitary confinement [to punish them] for the peaceful expression of his ideas.

Authorities subjected many detainees, including prisoners of conscience, to enforced disappearance, holding them in undisclosed locations and concealing their fate and whereabouts from their families. The authorities continued the pattern of executing members of ethnic minorities on death row in secret and concealing the whereabouts of their bodies, thereby subjecting their families to the ongoing crime of enforced disappearance.

The chain murders of Iran were a series of 1988–98 murders and disappearances of certain Iranian dissident intellectuals who had been critical of the Islamic Republic system. The murders and disappearances were carried out by Iranian government internal operatives, and they were referred to as "chain murders" because they appeared to be linked to each other. The victims included more than 80 writers, translators, poets, political activists, and ordinary citizens, and were killed by a variety of means such as car crashes, stabbings, shootings in staged robberies, and injections with potassium to simulate heart attack.

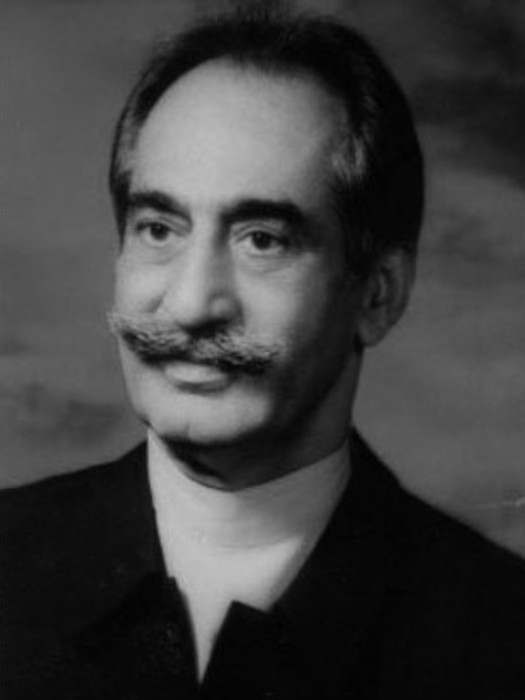

Dariush Forouhar

Forouhar and his wife, Parvaneh Forouhar, were overt opponents of Velayet-e-Faqih (clerical theocracy) and under continuous surveillance. They were assassinated in their home in 1998.

Parvaneh Forouhar

It is thought that the murders were provoked by Forouhar's criticism of human rights abuses by the Islamic Republic in interviews with Western radio stations that beamed Persian-language programs to Iran.

Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou

Kurdish politician and Kurdish leader. He was the Secretary-General of the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (KDPI) from 1973 until his assassination in 1989. Killed by three bullets fired at very close range.

Fereydoun Farrokhzad

A royalist, singer, actor, poet, TV and radio host, writer, humanitarian, and political opposition figure. Body was found in the kitchen of his apartment in Bonn, Germany. Killed violently, stabbed in face and upper torso.

Shapour Bakhtiar

Iranian politician who served as the last Prime Minister of Iran under the Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. He and his secretary were murdered in his home in Suresnes, near Paris by agents of the Islamic Republic.

Khamenei blamed foreign powers, stating "the enemy was creating insecurity to try to block the progress of Iran's Islamic system." Foreign correspondents believed the main suspects were likely to be conservatives opposed to Iran's more moderate President Mohammad Khatami reform agenda. In Iran, conservative daily newspapers also blamed "foreign sources intend on creating an environment of insecurity and instability in the country," for the killings. On 4 January 1999, the public relations office of the Ministry of Information "unexpectedly" issued a short press release claiming "staff within" its own Ministry "committed these criminal activities … under the influence of undercover rogue agents.

The authorities continued to commit the crime against humanity of enforced disappearance by systematically concealing the fate and whereabouts of several thousand political dissidents who were forcibly disappeared and extrajudicially executed in secret in 1988 and destroying unmarked mass gravesites believed to contain their remains. Security and intelligence forces threatened victims’ families with arrest if they sought information about their loved ones, conducted commemorations or spoke out.