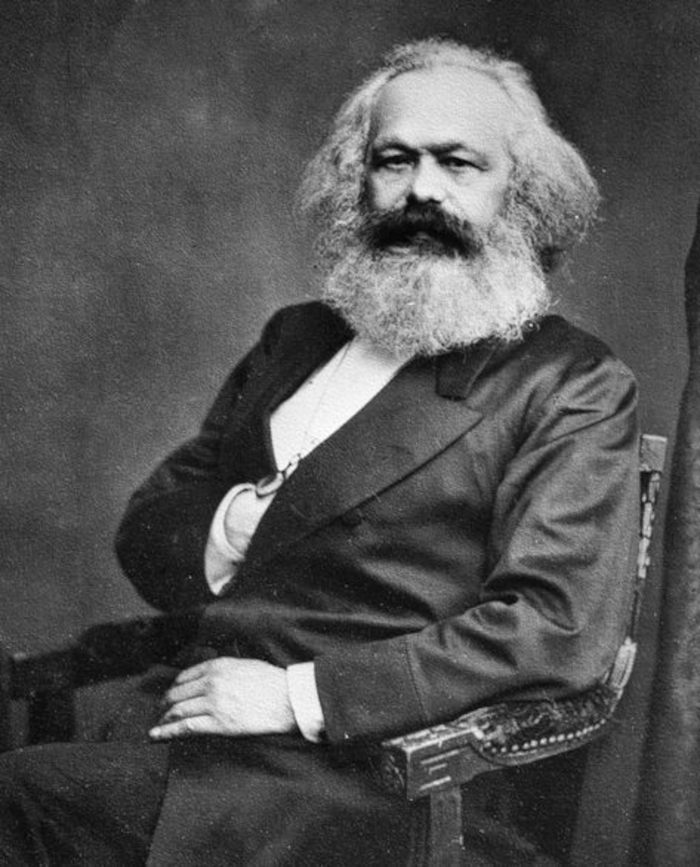

Karl Marx

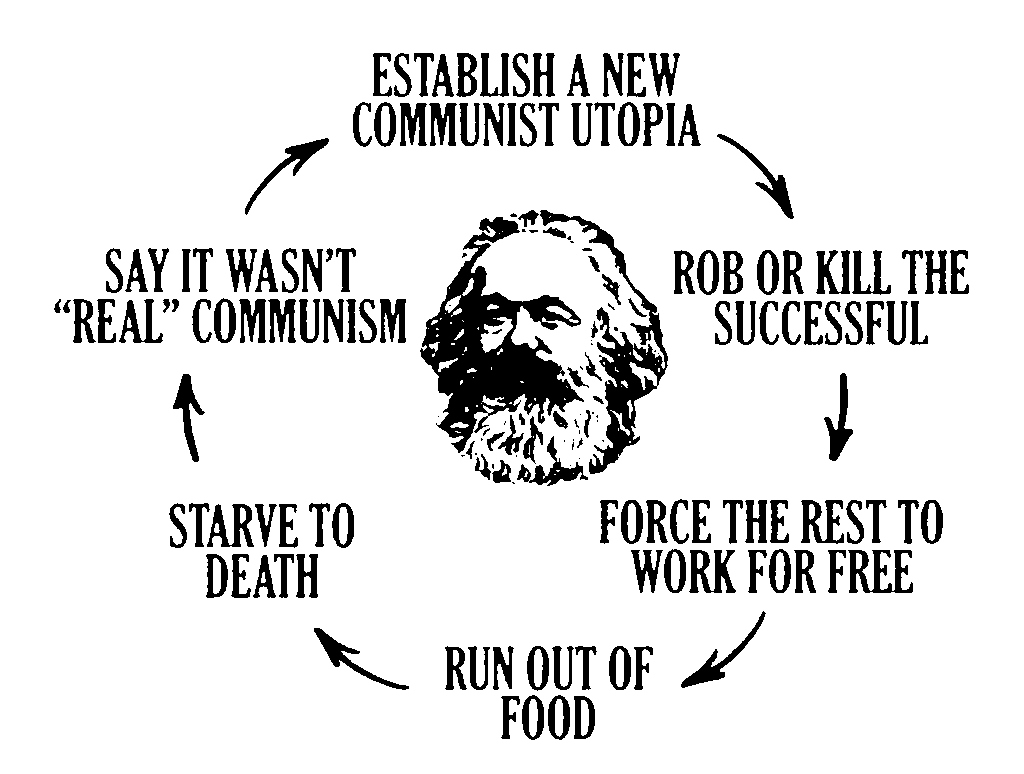

Karl Marx, founder of communism, was born in Germany 206 years ago. His ideology was used by mass killers like Stalin, Pol Pot and Mao Zedong. Christian Communists claim he's not responsible but his name is synonymous with death. Millions were killed by communist leaders across the world last century.

The extraordinary thing about Marxism is not its destructiveness – though, with 100 million deaths on its account, it is by far the most lethal ideology ever devised. No, the truly extraordinary thing is that, despite that monstrous record, it remains intellectually respectable. Marxists refuse to accept Marxism's role in dictatorships like North Korea.

Marxists are pretty much the only thinkers who accept no responsibility whatsoever for real-world approximations of their ideas.Kristian Niemietz, Institute of Economic Affairs.

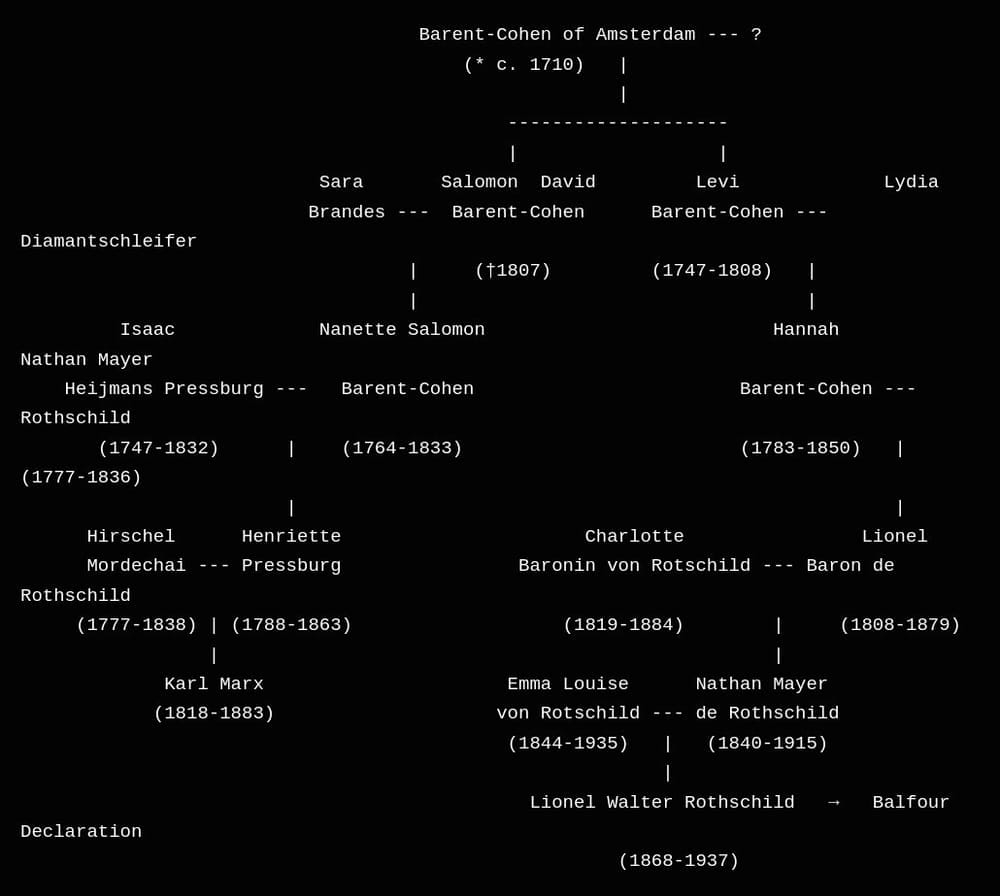

Marx's family was originally non-religious Jewish but had converted formally to Christianity before his birth. His maternal grandfather was a Dutch rabbi, while his paternal line had supplied Trier's rabbis since 1723, a role taken by his grandfather Meier Halevi Marx. But read about how Marx wrote about the religion that his father had abandoned:

What is the worldly religion of the Jew? Huckstering. What is his worldly God? Money. The chimerical nationality of the Jew is the nationality of the merchant, of the man of money in general.

His father was the first in the line to receive a secular education. He became a lawyer with a comfortably upper middle class income. He was interested in the ideas of the philosophers Immanuel Kant and Voltaire.

Marx was a hopeless economist, who struggled to grasp that goods did not have an intrinsic value, and that prices were a consequenc of demand rather than of bourgeois greed. Listen to the drivel he wrote in Das Kapital:

The sum of the values in circulation clearly cannot be augmented by any change in their distribution, any more than the quantity of the precious metals in a country can be augmented by a Jew selling a Queen Anne’s farthing for a guinea.

During the Napoleonic War of the Sixth Coalition, [Marx’s father] Hirschel Mordechai became a Freemason in 1813, joining their Loge L’Ètoile anséatique (The Hanseatic Star) in Osnabrück. His wife, Henriette Pressburg, was a Dutch Jew from a prosperous business family that later founded the company Philips Electronics.

Her sister Sophie Pressburg married Lion Philips. Lion Philips was a wealthy Dutch tobacco manufacturer and industrialist, upon whom Karl and Jenny Marx would later often come to rely for loans while they were exiled in London. Little is known of Marx's childhood.

Due to a condition referred to as a "weak chest", Marx was excused from military duty when he turned 18. While at the University at Bonn, Marx joined the Poets' Club, a group containing political radicals that were monitored by the police. Marx also joined the Trier Tavern Club drinking society where many ideas were discussed and at one point he served as the club's co-president. Although his grades in the first term were good, they soon deteriorated, leading his father to force a transfer to the more serious and academic University of Berlin. Marx's parents were concerned with his lifestyle and extravagance.

After receiving a letter from Karl in November 1837, his father responded in critical fashion:

Alas, your conduct has consisted merely in disorder, meandering in all the fields of knowledge, musty traditions by sombre lamplight; degeneration in a learned dressing gown with uncombed hair has replaced degeneration with a beer glass. And a shirking unsociability and a refusal of all conventions and even all respect for your father. Your intercourse with the world is limited to your sordid room, where perhaps lie abandoned in the classical disorder the love letters of a Jenny [Karl’s fiancée] and the tear-stained counsels of your father. ... And do you think that here in this workshop of senseless and aimless learning you can ripen the fruits to bring you and your loved one happiness? ... . As though we were made of gold my gentleman son disposes of almost 700 thalers in a single year, in contravention of every agreement and every usage, whereas the richest spend no more than 500.

Marx became interested in the recently deceased German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, whose ideas were then widely debated among European philosophical circles. During a convalescence in Stralau, he joined the Doctor's Club (Doktorklub), a student group which discussed Hegelian ideas, and through them became involved with a group of radical thinkers known as the Young Hegelians in 1837. Marx moved to Cologne in 1842, where he became a journalist, writing for the radical newspaper Rheinische Zeitung (Rhineland News), expressing his early views on socialism and his developing interest in economics. Marx criticised right-wing European governments as well as figures in the liberal and socialist movements, whom he thought ineffective or counter-productive. After the Rheinische Zeitung published an article strongly criticising the Russian monarchy, Tsar Nicholas I requested it be banned and Prussia's government complied in 1843.

Marx was not unique in being an anti-Semite of Jewish origin or in leaning on ethnic stereotypes (e.g., he spoke of “lazy Mexicans” who would benefit by being politically dominated by the United States). He can be found abusing his rivals with ethnic slurs, sometimes practically rococo in their ornamentation. (His letter to Engels denouncing “Der jüdische N*****” Ferdinand Lassalle, which includes spiteful racial speculations about the man’s ancestry, is the most infamous example.) But Judaism was hardly an afterthought to the father of socialism. It is notable that one of Marx’s first high-profile contributions to intellectual life was “On the Jewish Question,” which is full of anti-Jewish invective: “What is the worldly cult of the Jew? Huckstering. . . . The bill of exchange is the real god of the Jew.

In 1843, Marx became co-editor of a new, radical left-wing Parisian newspaper, the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher. Based in Paris, the paper was connected to the League of the Just, a utopian socialist secret society of workers and artisans (later under Marx's influence) professing Christian communism. Marx attended some of their meetings. On 28 August 1844, Marx met the German socialist Friedrich Engels at the Café de la Régence, beginning a lifelong friendship. Marxism was to be based in large part on three influences: Hegel's dialectics, French utopian socialism and British political economy.

Unable either to stay in France or to move to Germany, Marx decided to emigrate to Brussels in Belgium in February 1845. However, to stay in Belgium he had to pledge not to publish anything on the subject of contemporary politics. In April 1845, Engels moved from Barmen in Germany to Brussels to join Marx and the growing cadre of members of the League of the Just now seeking home in Brussels, In mid-July 1845, Marx and Engels left Brussels for England to visit the leaders of the working-class movement Chartists.

Chartist leaders: Ernest Charles Jones (pioneer of the modern Labour movement) and George Julian Harney (associated with socialism, and universal suffrage) knew Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels personally.

I knew Engels, he was my friend and occasional correspondent over half a century. It was in 1843 that he came over from Bradford to Leeds and enquired for me at the Northern Star office. A tall, handsome young man, with a countenance of almost boyish youthfulness, whose English, in spite of his German birth and education, was even then remarkable for its accuracy. He told me he was a constant reader of the Northern Star and took a keen interest in the Chartist movement. Thus began our friendship over fifty years ago.George Julian Harney

While residing in Brussels in 1846, Marx continued his association with the secret radical organisation League of the Just (originally form as an an egalitarian international revolutionary fellowship organisation named the League of Outlaws). As noted above, Marx thought the League to be just the sort of radical organisation that was needed to spur the working class of Europe toward the mass movement that would bring about a working-class revolution. However, to organise the working class into a mass movement the League had to cease its "secret" or "underground" orientation and operate in the open as a political party. Members of the League eventually became persuaded in this regard. Accordingly, in June 1847 the League was reorganised by its membership into a new open "above ground" political society that appealed directly to the working classes.

Marxism is a social, economic and political philosophy that analyses the impact of the ruling class on the labourers, leading to uneven distribution of wealth and privileges in the society.

This new open political society was called the Communist League. Both Marx and Engels participated in drawing up the programme and organisational principles of the new Communist League. In late 1847, Marx and Engels began writing what was to become their most famous work – a programme of action for the Communist League. Written jointly by Marx and Engels from December 1847 to January 1848, The Communist Manifesto was first published on 21 February 1848. Later that year, Europe experienced a series of protests, rebellions, and often violent upheavals that became known as the Revolutions of 1848. In France, a revolution led to the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the French Second Republic. Marx was supportive of such activity and having recently received a substantial inheritance from his father (withheld by his uncle Lionel Philips since his father's death in 1838) of 6,000 allegedly used a third of it to arm Belgian workers who were planning revolutionary action. The Belgian Ministry of Justice accused Marx of it, subsequently arresting him and he was forced to flee back to France, where with a new republican government in power he believed that he would be safe.

Temporarily settling down in Paris, Marx transferred the Communist League executive headquarters to the city and also set up a German Workers' Club with various German socialists living there. Hoping to see the revolution spread to Germany, in 1848 Marx moved back to Cologne where he began issuing a handbill entitled the Demands of the Communist Party in Germany, in which he argued for only four of the ten points of the Communist Manifesto, believing that in Germany at that time the bourgeoisie must overthrow the feudal monarchy and aristocracy before the proletariat could overthrow the bourgeoisie.

The book Der preußische Regierungsagent Karl Marx by Wolfgang Waldner, suggests that initially Marx worked as a police spy for the Prussian regime. Waldner mentions the fact that Marx married Jenny von Westphalen in 1843. She came from a wealthy Prussian family. Her brother was Ferdinand von Westphalen, who was Prussian Minister of the Interior from 1850-1858. Ferdinand, Marx’s brother-in-law, was regarded as “reactionary”, who ran a vast spy network which kept tabs on dissidents.

On 1 June, Marx started the publication of a daily newspaper, the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, which he helped to finance through his recent inheritance from his father. Despite contributions by fellow members of the Communist League, according to Friedrich Engels it remained "a simple dictatorship by Marx". Meanwhile, the democratic parliament in Prussia collapsed and the king, Frederick William IV, introduced a new cabinet of his reactionary supporters, who implemented counter-revolutionary measures to expunge left-wing and other revolutionary elements from the country. Consequently, the Neue Rheinische Zeitung was soon suppressed, and Marx was ordered to leave the country.

Perhaps the most pronounced and consistent aspect of Marx’s ideology was his extreme and radical hatred of Russia [the last bastion of Christian civilisation..]... He and Engels regarded Russians and Slavs in general as subhuman (völkerabfall) barbarians. Had he lived to see his ideological heirs Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Grigory Zinoviev butcher them by the millions, he would no doubt have cackled in orgasmic joy at the horrors visited upon them; men, women and children.

Marx returned to Paris, which was then under the grip of both a reactionary counter-revolution and a cholera epidemic, and was soon expelled by the city authorities, who considered him a political threat. With his wife Jenny expecting their fourth child and with Marx not able to move back to Germany or Belgium, in August 1849 he sought refuge in London. Marx moved to London in early June 1849 and would remain based in the city for the rest of his life. The headquarters of the Communist League also moved to London . In the early period in London, Marx committed himself almost exclusively to his studies, such that his family endured extreme poverty. His main source of income was Engels, whose own source was his wealthy industrialist father.

In his darkest moments, Marx, the man who called for a world revolution spent his time attacking the pus-filled boils on his bottom with a cut-throat razor. A hard-drinking, chain-smoking man, scruffy and shambolic, cadging money from his friends and cheating on his wife with his housekeeper.

Marx was afflicted by poor health (what he himself described as "the wretchedness of existence"). Marx suffered from a trio of afflictions. A liver ailment, probably hereditary, was aggravated by overwork, a bad diet, and lack of sleep. Inflammation of the eyes was induced by too much work at night. A third affliction, eruption of carbuncles or boils, "was probably brought on by general physical debility to which the various features of Marx's style of life – alcohol, tobacco, poor diet, and failure to sleep – all contributed.

In 2007, a retro-diagnosis of Marx's skin disease was made by dermatologist Sam Shuster of Newcastle University and for Shuster, the most probable explanation was that Marx suffered not from liver problems, but from hidradenitis suppurativa, a recurring infective condition arising from blockage of apocrine ducts opening into hair follicles. Shuster went on to consider the potential psychosocial effects of the disease, noting that the skin is an organ of communication and that hidradenitis suppurativa produces much psychological distress, including loathing and disgust and depression of self-image, mood, and well-being, feelings for which Shuster found "much evidence" in the Marx correspondence.

Whilst working on three volumes of Das Kapital, Marx complained to friends about the 'carbuncles on my posterior and near the penis, the final traces of which are now fading, but which made it extremely painful for me to adopt a sitting and hence a writing posture..

Professor Shuster went on to ask himself whether the mental effects of the disease affected Marx's work and even helped him to develop his theory of alienation. Marx developed a catarrh that kept him in ill health for the last 15 months of his life. It eventually brought on the bronchitis and pleurisy that killed him dying a stateless person at age 64.

Karl Marx grave at Highgate Cemetery, London has been attacked on numerous occassions including a 1970s pipe bomb blowing his nose off. Marx Grave Trust have deployed 24-hour video surveillance around the grave. Since its construction, the tomb has become a place of veneration for Marx's followers, including some, such as the anti-apartheid activist Yusuf Dadoo and the founder of the Notting Hill Carnival Claudia Jones, who have been buried nearby.

Family and friends in London buried his body in Highgate Cemetery (East), London, in an area reserved for agnostics and atheists. The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) had the monument with a portrait bust by Laurence Bradshaw erected and Marx's original tomb had only humble adornment. Black civil rights leader and CPGB activist Claudia Jones was later buried beside Karl Marx's tomb. Marx was a fanatic whose ideas inspired some of the cruellest regimes in history, from Stalin's Siberian gulags to the killing fields of Cambodia. From the Russian Revolution in 1917 to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, one regime after another tried to put his revolutionary ideas into practice.

There is only one way in which the murderous death agonies of the old society and the bloody birth throes of the new society can be shortened, simplified and concentrated,' wrote Marx in 1848, 'and that way is revolutionary terror'. Marx a year later, addressing his conservative adversaries: 'We have no compassion and we ask no compassion from you,' he writes. 'When our turn comes, we shall not make excuses for the terror..

Yet, to his admirers who include the ex-Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, who called him a 'great economist', and the Shadow Chancellor, John McDonnell, who has named Das Kapital as his favourite book he remains a visionary prophet whose ideas will, one day, lead mankind to a classless utopia. The Soviet Union's founding father, Lenin, wrote several books about Marxist thought, which he described as 'the only correct revolutionary theory'. Mao believed that Marx's ideas represented 'the good, the true and the beautiful'. Even the Khmer Rouge thought their new Cambodia a classless society with no elites, no banks and no private property was the fulfilment of Marx's vision. The best example is Stalin. As the U.S. historian Stephen Kotkin has shown, the Soviet dictator was not a monster who happened to be a Marxist. He was a monster because he was a Marxist. As a young man, Stalin studied Marx's theories with obsessive dedication. Then, after winning power, he put them into practice.

In Judaism and Christianity, the wellsprings of mainstream Western politics, individual life is sacred, because man is made in God's image. But, for Marxists, the individual is irrelevant. Man is merely the servant of history. All that matters is the collective, the grand sweep. And if that means some people Russian landowners, Chinese merchants, Cambodian teachers, Cuban dissidents end up in mass graves, prison camps or psychiatric hospitals, that is just their tough luck. Marx's followers cast aside not only history and tradition, but tens of millions of lives. In the name of progress, they slaughtered men, women and children like animals in an abattoir. And in almost every corner of the Earth, mass graves testify to the diabolical power of Marx's vision.

Show me a communist regime and I’ll show you labour camps, firing squads and torture chambers. It was the same story every time, from Albania to Angola, from Benin to Bulgaria, from Cuba to Czechoslovakia.Daniel Hannan, Telegraph 5/5/18

It’s well known that Communism killed 100 million people but few are aware of the obsession Communism’s founder Karl Marx had with the Devil. Marx’s ideas came with many diabolical flaws, perhaps none so deadly as his naive and unfounded optimism about the perfectibility of man. If 20th-century Communist experiments taught the world anything, it is that humans, by their very nature, will always seek to oppress one another most notably at nexus of a revolution, when traditional hierarchies are torn down. While the devilish fruit of Marxism is visible to anyone with eyes to see it, what many people do not know about Karl Marx is that he had an explicit interest even preoccupation with devilry, which had a profound influence on all of his thinking. Over the years, a number of writers have sought to shed light on Karl Marx’s obsession with the Devil. The bizarre discovery was first made by Marx’s original biographer Franz Mehring, who was so taken aback by what he found that he advised Marx’s youngest daughter Eleanor to keep the revelation from going public.

Two books that ultimately did make these revelations public were Marx: A Biography (1968) and Marx and Satan (1971), both penned by British intellectual Robert Payne. In 1976, Romanian pastor Richard Wurmbrand added to this catalogue with his popular tome Marx & Satan. The most recent publication on the topic is The Devil and Karl Marx (2020), written by Paul Kengor, professor of political science at Grove City College and executive director of the Institute for Faith and Freedom. Following his book’s release, Kengor sat down for a fascinating and wide-ranging discussion on the subject with Albert Mohler, President of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. In introducing Kengor and his treatise, Mohler summarises that “even as [Marx] sought in every way possible to kill off God, and even organised religion, he had enormous sympathy for the Devil, and clearly, in some sense, believed in the Devil… he clearly believed in the personification of evil.”

God is on your side? Is He a Conservative? The Devil's on my side, he's a good Communist..Joseph Stalin Said to Winston Churchill in Tehran, November 1943, as quoted in Fallen Eagle: The Last Days of the Third Reich (1995) by Robin Cross, p. 21 - Contemporary witnesses.

Kengor acknowledges that, as with any writer or poet, so with Marx’s musings on Satan, discerning his precise meaning sometimes involves guesswork: “He’s internalising; he’s projecting; it’s what he believes; it’s what a character believes…” Even so, Kengor notes, Marx’s fixation on this theme is “very reflective of what he believes”. Kengor opens The Devil and Karl Marx with quotations from two of Marx’s early poems:

Thus Heaven I’ve forfeited, I know it full well.

My soul, once true to God, Is chosen for Hell.The Pale Maiden, 1837

Look now, my blood-dark sword shall stab

Unerringly within thy soul…

The hellish vapours rise and fill the brain,

Till I go mad and my heart is utterly changed.

See the sword—the Prince of Darkness sold it to me.

For he beats the time and gives the signs.

Ever more boldly I play the dance of death.The Player, 1841

“These poems and his plays, they’re filled with destruction, death, suicide pacts,” Kengor explains — before offering a shocking and little-known historical fact: “Marx had two daughters who killed themselves in suicide pacts with their husbands”. Kengor notes that another theme to emerge in Marx’s plays and poems is that, metaphorically speaking, “Marx wanted to burn down the house.”

Marx and his characters in the end of these plays, they are standing there in the pit of these embers, flames all around them.

Indeed, a sombre observation made by multiple Marx biographers is that his favourite quote in all of literature comes from the mouth of Mephistopheles, a demon from German folklore, who in Goethe’s tragedy Faust declares, “Everything that exists deserves to perish.” “Imagine that,” Kengor exclaims. “That was Marx’s favourite.”. Karl Marx’s parents were Jewish, however his father Heinrich converted to a liberal brand of Lutheranism, mostly for social convenience and career mobility, in an era in Germany. Even so, Kengor explains, in letters to his then-teenaged son, Heinrich urged Karl to become religious so that he had something to believe in other than himself.

I quote at length this ominous letter, March 2nd, 1837, from his father,” Kengor explains, paraphrasing: “That heart of yours, son, what’s troubling it? Is it governed by a demon? Is it governed by a spirit? And is that spirit heavenly or is it Faustian?

Kengor and Mohler agree that throughout his adult years, Karl Marx’s life was marked by a deep misanthropy — a hatred for humanity. “He’s calling for humanity to unite in this Communist movement,” Mohler remarks, drawing out the irony — “but he hates humanity, and it began with his own family.”, Marx was “a very angry man,” Kengor concurs. “All the people around him couldn’t stand him. And Engels was one of the only people that was really able to hang in there with him at all.” Kengor explains that Marx funded his writing career by draining the financial resources of his parents until “they finally cut him off and then it was left to Engels to subsidise him”. "Engels felt bad for Marx’s family,” Kengor reflects. “Marx refused to get a job. He refused to work. Marx’s poor, long-suffering wife, Jenny… expressed the wish that Karl would start earning some capital rather than just writing about capital.”, Children in the Marx household died, arguably, from malnutrition — exposure to the elements”.

A significant and “toxic, pernicious” influence on Karl Marx during his formative years, Kengor notes, was his doctoral advisor Bruno Bauer. Bauer was a theology professor and, rather ironically, an atheist — which was not an entirely impossible combination given the waywardness of 19th-century German Protestantism. The pair began plans for a journal called Atheistic Archives, which never came to fruition. Kengor shares that on one particular Palm Sunday, Bauer and Marx rode into a German village on donkeys, mocking Christ’s entrance into Jerusalem. They also scandalised their class by getting drunk and disrupting a church service. Kengor and Mohler concur that, while it is increasingly common today for people to try and marry Christianity with various forms of Marxism, Socialism or Communism, these are unholy and ultimately impossible unions. “Like Marx said, Communism begins where atheism begins,” Kungor warns.

The discussion between Paul Kengor and Albert Mohler closes with some sober reflections on Marxism’s tentacles in the 21st century. Kengor refers to one of the closing lines in The Communist Manifesto, in which Marx and Engels state that “their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions”. Thus, they observe, true Marxism is not merely about economics, but all of society. “They realised that you had to take out God,” Kengor explains. “You had to remove God.”. “Once you raze that foundation… then you can stand there like Marx did in the embers of that burnt-down house with your fist in the air, [declaring], ‘Everything that exists deserves to perish.’ And now we can begin our world anew.” “They knew that you had to abolish not just property, not just capital, not just the family — you needed to abolish religion as well” Kengor concludes. Kengor and Mohler affirm that Critical Theory — which they agree is “the more academic term for Cultural Marxism” — is the direct descendant and present-day manifestation of Marx’s ideas. Kengor ends the discussion highlighting a quote often attributed to former U.S. President Ronald Reagan:

A Communist is somebody who reads Marx. An anti-Communist is someone who understands Marx

All Marxist “theory” begins by believing it uniquely knows what human beings really are (socio-spiritual beings), into what they have been thrown (a mundane world of property ownership, imposed identity, and suffering through scarcity), and to what we must return (a truly social society that transcends individualism). Because Marxists fundamentally believe they know the true and secret socio-spiritual nature of humans whereas (demonic, Demiurgic) social forces have conditioned everyone else not to know them, they feel uniquely entitled to power for the purpose of remaking man into who he is. This explains most of their behavior. The ultimate goal of Marxism isn’t economic, political, or social control, as most would believe. Those are merely means to its end. Its ultimate goal isn’t even power, though it worships power as the constitutive force of reality. Its ultimate goal is to direct the socio-spiritual evolution of Man. Socio-spiritual in the sense that Man’s true spiritual nature manifests in his social relations. This is the idea of the “New Man” Marxists always speak of. He is Man spiritually evolved to remember who he truly is, a truly social and creative being that is one with all others in his species and, indeed, all of Nature.

This means that Marxism is a particularly nasty, vindictive, and deceptive form of Gnostic theosophy, a cult religion. Laid bare of all its details in whatever form, economic, racial, sexual, whatever, it is a drive to seize power to direct the spiritual evolution of Man. Everything else it argues is either rationalization or excuse, none of it is real or legitimate because none of it does anything but serve its actual purpose in whichever moment of resistance it finds itself in. What is meant by “direct the socio-spiritual evolution of Man”? In a word, eugenics. Marxism intrinsically practices eugenics, though not necessarily on the “crude” physical level (mundane) but on the more refined spiritual level they believe they uniquely understand. In practice, a lot of the crude part comes out by necessity. The goal is to prune out of mankind those unfit to evolve spiritually to the higher collectivist levels and to transform the rest into socio-spiritual Marxists.

In theosophical cults, Man is believed to have forgotten who he really is by virtue of some Fall. He is truly Spirit and One with God and thinks himself otherwise because of the distortions of his conditions: materialist, social, economic, or otherwise. He has forgotten this because he lacks “God’s wisdom” (theo-sophy) to know who—and what—he truly is, which is a spiritual being at one with the One. Since this is true for everyone all at once, no one is truly separate from anyone else. All is One; All are One. To be an individual in this circumstance is to reject Oneness in favor of individualism, which is Man’s Fall. The goal of theosophical religious cults is to seize enough power over their adherents to remind them of who they “really are,” which brings them to “at-One-ment” (atonement for their false separation from God) by obliterating their allegedly false consciousness of themselves and Man. They misunderstand themselves and thus misunderstand the society and world around them. Theosophists aim to remind them of who they “truly are” and bring them back to Oneness of spirit and being. They can be kindly enough, but in the end, they are tyrannical because humanity can only evolve as a whole if their presumptions about the nature of reality and Man are true.

These cults are ultimately Gnostic. As the second-century Valentinian Gnostic Theodotus put it: “It is not, however, the bath [baptism] alone that makes free, but knowledge [gnosis] too: who we were, what we have become, where we were, where we have come to be placed, where we are tending, what birth is, and what rebirth.” Theosophists believe we were Spirit but have become mortal; we were in Paradise in perfect union with God but have been thrown into this mundane world; we are tending toward spiritual awakening or destruction; and birth is a Fall and rebirth is accepting their Gnostic cult beliefs and practices. It isn’t all just ancient heresy or New Age hippie nonsense. Marxism is cut from precisely this cloth. The old Gnostic heresies place the Fall of Man in the Sin of Adam, obviously, blaming the wrath of God for flinging us out of Paradise and our inheritance into this world of work, pain, toil, and death—as individuals, separated from God and Eden. Their belief was that the Serpent in Genesis told the truth, and the God in Genesis is not God but a demonic Demiurge, builder of the world, imprisoner of his spiritual brethren in Man.

The framework is the same in every case, and the details only vary a little as needed. A demonic superpower—the Demiurge, the bourgeoisie, whites, “cis” straight people, or whatever—orders and rules the world for itself. It did this by illegitimately taking a step toward godhood, separating itself from the All, and locked out those who are truly innocent and knowing. It is the projection of Satan onto the godly and godliness onto Satan. On the first page of the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels say the whole of their program is put in a word: “oppressor versus oppressed.” The privileged establish themselves as separate and deserving while the innocent are excluded from “godlike” knowing and punished severely when they take a bit of the fruit of the tree of knowledge. The Gnostic theosophical myth is that the innocent are excluded by powers who broke away from the unified totality of being to assert their individuality. Maybe they have done this through claiming deity themselves as Creator of the (mundane and Fallen) world, or in a socio-spiritual sense through private property, racial status, social status otherwise, etc. Because these deign to be God but are not, they are jealous and wrathful of anyone who might approach the “hidden truth” of gnosis, which would break their spell and end their illegitimate power. They hide and suppress the “truth” and punish anyone who seeks or stumbles upon it.

The theosophical gnostics know otherwise, though. They know the “gods” are false and that God as a unified totality is real and, in fact, not distinct from themselves. They are therefore spiritually or socio-spiritually advanced but oppressed and must shepherd Man to Liberation. This amounts to a revolution, either of Heaven and Earth or of society, depending on the locus of their beliefs, but it’s all the same. Marxism, Race Marxism, Queer Marxism, and the rest are identical in this form. They are all theosophical religious cults pretending not to be. Marx argued that religion exists because we are unhappy and alienated in our economic lives. It drugs people into acceptance of their lot. While living in London in the nineteenth century, he saw numerous opium dens filled with people seeking to dull their pain. He thought that this was a perfect metaphor for religion. Marx had been deeply influenced by the German anthropologist and philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872), who argued that God is a human projection. The idea of God serves to sustain people through the hardships of life.

Marx considered every society to be based on an economic foundation (such as capitalism). The foundation is kept in place by institutions such as law, education, religion, the family and political bodies. All these need to be exposed as exploitative and pulled down. Revolutionary activism was the priority. Many Christians (and others) have naïvely read back into Marx their own desire to see greater economic and social justice. But Marx should be allowed to speak for himself. Please read Das Kapital for yourself. And then read an immensely powerful book by Paul Kengor, The Devil and Karl Marx: Communism's Long March of Death, Deception, and Infiltration. The first generation of Marxists pushed for violent revolution. Those associated with the Frankfurt School would promote cultural revolution. Later advocates of Critical Theory would attack Marxist truth claims. But a common motif recurs. Religion is a false consciousness that puts a brake on the activism that is needed to liberate oppressed groups. Religion must not be tolerated.